Home » Articles posted by Simon Mayers

Author Archives: Simon Mayers

English Methodists and the Myth of the Catholic Antichrist (c. 1755 – 1817)

Paul’s second epistle to the community at Thessalonica warned that the second coming of Christ will be preceded by the appearance of ‘the man of sin’ (or ‘the man of lawlessness’), who will work false miracles and exalt himself over God, setting himself up in God’s Temple, all in accordance with the plans of Satan (2 Thess 2:1-17). The ‘man of sin’ was subsequently linked to the Antichrist mentioned in John’s first and second epistle (1 John 2:18-22, 4:3, 2 John 1:7). Various diabolic figures from the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelation have also been interpreted as relating to the Antichrist. These allusions to a diabolic character were fleshed out over time. According to Norman Cohn (1975), ‘over the centuries new and terrible anxieties began to make themselves felt in Christian minds, until it came to seem that the world was in the grip of demons and that their human allies were everywhere, even in the heart of Christendom itself.’ The Antichrist was regarded as an authentic manifestation of evil, who would lead Satan’s forces in a cosmic war against the followers of Christ. The Antichrist was intertwined with millenarian expectations of the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth. The arrival of the Antichrist, as Cohn (1957) observed, was considered no mere ‘phantasy about some remote and indefinite future but a prophecy which was infallible and which at almost any given moment was felt to be on the point of fulfilment’. [1]

The Seven-Headed Beast (Silos Apocalypse, Illuminated Manuscript) [Wikimedia Commons]

‘A wild beast coming up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns’

In English-Methodist discourses during the eighteenth century, it was often the Catholic popes – sometimes individually, sometimes collectively – who were mythicised as ‘the Antichrist’. The tone for these discourses about ‘Antichrist’ was set by the original founders and leaders of the Methodist movement, John Wesley (1703 – 1791) and Charles Wesley (1707 – 1788), both of whom were enthusiastic millenarians.

John Wesley’s general ambivalence and prejudice towards Roman Catholicism has been well documented by David Butler (1995), but it is specifically to John Wesley’s construction of the so-called ‘Romish Antichrist’ that we now turn. According to Butler, it was in his commentary on Revelation in his Explanatory Notes on the New Testament (1755) that John Wesley recorded his ‘oddest thoughts on the Papacy’. John Wesley’s preface to this section of his Explanatory Notes records how he despaired of understanding much of Revelation until he encountered ‘the works of the great Bengelius’, (i.e., Johann Bengel’s Gnomon, published in 1742), the reading of which ‘revived’ his hopes of understanding ‘even the prophecies’ recorded in the Book of Revelation. According to John Wesley, much of his commentary on Revelation was partly translated and abridged from observations found in Bengel’s Gnomon, albeit he allowed himself ‘the liberty’ to alter some of Bengel’s observations, and to add a few notes where he felt that Bengel’s account was incomplete. Where Johann Bengel ends and John Wesley begins is not always clear, but that they were seemingly much in agreement – at least in the passages that John Wesley derived or lifted from Bengel – seems reasonably certain.

John Wesley believed that the role of Antichrist, ‘the beast with seven heads’, was not assigned to just a single individual, but to ‘a body of men’ at some moments in history, and ‘an individual’ at others, which he summarised as ‘the papacy of many ages’. In particular, he seems to have had in mind all popes since the beginning of the papacy of Gregory VII in 1073. He regarded this fantastical ‘beast’ to be no mere legend but a real and imminent danger. Commenting on Revelation 13:1 (‘and I stood on the sand of the sea, and saw a wild beast coming up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten diadems, and upon his heads a name of blasphemy’), John Wesley stated that ‘O reader! This is a subject wherein we also are deeply concerned; and which must be treated, not as a point of curiosity, but as a solemn warning from God. The danger is near.’ According to John Wesley, the sea that the Antichrist was prophesied to emerge from was not ‘the abyss’ but rather ‘Europe’, and ‘the beast’ was ‘the Romish papacy, as it came to a point six hundred years since, stands now, and will for some time longer.’ John Wesley was not, it seems, entirely sure about the exact arrival of the Antichrist, suggesting that the Antichrist arrived some 600 to 700 years previously (from the perspective of his writing in the 1750s), at some point between the beginning of the papacy of Gregory VII and the conclusion of the papacy of Alexander III (i.e., between 1073 and 1181), though he fixated primarily on Gregory VII. Butler convincingly suggests that Wesley’s strongest suspicion was that Gregory VII was the original manifestation of ‘the beast’. This seems to be confirmed by a closer examination of Wesley’s commentary on Revelation. In his comment on Revelation 13:1, Wesley stated that ‘whatever power the papacy has had from Gregory VII, this the Apocalyptic beast represents’. And in his commentary on Revelation 17:11, Wesley states that: ‘the beast consists as it were of eight parts. The seven heads are seven of them; and the eighth is his whole body, or the beast himself … The whole succession of popes from Gregory VII are undoubtedly antichrist. Yet this hinders not, but that the last pope in this succession will be more eminently the antichrist, the man of sin; adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit. This individual person, as a pope, is the seventh head of the beast; as the man of sin, he is the eighth, or the beast himself.’ Despite his warnings about the danger posed by ‘the beast’ in his Explanatory Notes in 1755, John Wesley seems to have believed that the beast would eventually be defeated in 1836 (following the chronology of Johann Bengel). In his commentary on Revelation 17:10, he speculates simply that in 1836, ‘the beast [will be] finally overthrown’. In fact, it seems that just 22 years later, John Wesley was already confident that the power of ‘the beast’ was already in decline. According to Butler, Wesley wrote a letter to Joseph Benson (another Methodist minister) in 1777, stating that ‘the Romish Anti-Christ is already so fallen that he will not again lift up his head in any considerable degree. … I therefore concur with you in believing that his tyranny is past never to return’. [2]

Two pages from John Wesley’s Explanatory Notes upon the New Testament, 12th edition

Around the same time that John Wesley was finishing his Explanatory Notes on the New Testament, his brother, Charles Wesley, also made reference to the ‘Romish Antichrist’. In April 1754, he wrote a letter to an unknown correspondent. In this apocalyptic letter, Charles Wesley referred to the ‘labyrinth’ of ‘scriptural Prophecies’ that God had guided him through, and the arrival of the ‘Kingdom of our Lord in its fulness upon earth’ after certain key events: ‘the conversion of God’s antient people the Jews, their restoration to their own land; [and] the destruction of the Romish Antichrist & of all the other adversaries of Christ’s kingdom’. [3]

Kenneth Newport (1996), in his comprehensive survey of Methodist millenarianism (mostly premillennialism), identifies a number of other Methodist preachers who referred or alluded to the ‘Roman’, ‘Rome’ or Catholic ‘Antichrist’. For example, according to Newport, Joseph Sutcliffe (1762 – 1856), a preacher appointed by John Wesley to the Redruth Circuit in 1786, and the author of several works including a commentary on scripture and a 25-page pamphlet on the ‘glorious millennium, and the second coming of Christ’ (1798), constructed an elaborate millennial narrative combining elements of pre- and post-millennialism (with Christ’s second coming prior to his thousand-year reign on Earth, but with Christ returning to and ruling the earthly Church from heaven, and the millennium not entirely free from the vices and wickedness of earlier times, and with the millennium followed by one final cataclysmic battle between Jesus and Satan at its conclusion). In Sutcliffe’s narrative, the Roman ‘Antichrist’ (‘the pagan and the papal beast’) is defeated, the Jews embrace Christianity, and play a special eschatological role in helping to convert ‘the Turks, Tartars, Persians, and the numerous nations of the African shores’; ‘dwelling among all commercial nations, and being perfectly acquainted with their manners, customs, languages and religions, they [the Jews] are already arranged as an army of missionaries’. Later, Satan attacks the Jews, who by then are in Jerusalem, but Satan is defeated when Christ appears in visible form to slay his enemies. This is all expected to occur in the nineteenth century (beginning with the final defeat of the Antichrist circa 1820 and the battle against Satan in Jerusalem circa 1865). Then, after a thousand years of Christ’s rule of the earthly Church from the Celestial Court (i.e., a temporary paradise on Earth, a kingdom ruled from heaven, rather than located in heaven), Satan will escape his thousand-year imprisonment in the ‘bottomless pit’ to return for one last cosmic battle, but will be defeated by ‘the Lord Jesus’ who returns from heaven in ‘flaming fire’. After this, there will be the final judgement, the destruction of the wicked, and the resurrection of the righteous in the everlasting heavenly kingdom of God (presumably circa 2865). And according to Newport, Thomas Coke (1747 – 1814), the co-founder of Methodism in America and the first Methodist bishop, also developed a vibrant millenarian narrative in his Commentary on the Holy Bible (1803), in which the Antichrist already rules the Earth (presumably unbeknownst to most people), and has done so since the year 606 CE, but the Antichrist will be destroyed after his 1,260 year reign, in circa 1866, after which the Jews and Gentiles will all embrace Christianity, and the millennium will begin. [4]

Thomas Taylor (1738 – 1816), an influential Methodist preacher and friend of John Wesley, also argued that the ‘great Anti-christ’ was the ‘church of Rome’, in his Ten Sermons on the Millennium; or, the Glory of the Latter Days (1789). According to Taylor, ‘a glorious time’ was coming, when ‘Jesus will reign, and every knee shall bow, and every tongue shall confess him to be Lord’. This blessed time will, Taylor suggested, involve the ‘destruction of Antichrist’, ‘the chaining of the dragon’, ‘wars and fighting ceasing’ and ‘the gathering in of the Jews’, among other events. Turning to the subject of Antichrist, Taylor observed that ‘every person, persons or thing, which oppose Christ, may be termed Anti-christ’. According to Taylor, the Antichrist thus consists of many groups, including ‘the Jews’, ‘the Turks’ and ‘Socinians’. But for Taylor, the ‘great Antichrist’ was the Catholic Church. For example, whilst he summed up the reasons for ‘the Jews’ being on the list in just one sentence (‘the opposers of Christ, in that they reject his government, will not have this man to reign over them, and thereby judge themselves unworthy of everlasting life’), and similarly ‘the Turks’ and ‘Socinians’ in one sentence apiece, the Catholic Church received several pages of criticism. According to Taylor, ‘but what is most generally understood by that term’ [i.e., Antichrist], ‘and what the scriptures in very clear terms mark out, as well as history, for Antichrists are, the doctrine, hierarchy and discipline of the church of Rome. The Pope and Cardinals, together with the whole herd of secular and regular priests and begging friars, joined with their whole train of legends for doctrines, may be said to be the great Antichrist’. Taylor outlined over several pages of the sermon what he considered to be the sins of the ‘church of Rome’, including as highlights, ‘infallibility’, ‘transubstantiation’, ‘praying to the dead’, ‘purgatory’, ‘priestly absolution’, ‘persecutions’, ‘torture’ and ‘the Inquisition’. He suggested that in its ‘superstitious discipline’ and ‘horrid cruelties’, the ‘church of Rome’ was the ‘whore of Babylon’. [5]

Significantly, Adam Clarke, a prominent Methodist preacher and bible scholar from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, whose anti-Judaism and anti-Catholicism I examined as part of a collaborative project between the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Manchester and the John Rylands Research Institute, also embraced many hostile myths and stereotypes about Catholics (and Jews), but rejected the millenarian ideas of the previously discussed Methodists. Adam Clarke was born c. 1760 – 1762 (the exact year being unknown) in Londonderry. He died of cholera in London on 28 August 1832. Clarke met John and Charles Wesley at the Kingswood school in Bristol when he was approximately eighteen years of age, and was appointed by them to preach at Bradford on Avon in Wiltshire. His circuit soon extended to other towns and villages, and he was later assigned to the London Circuit. He was elected three times to the Presidency of the Methodist Conference and was widely respected as a preacher and scholar.

Unlike the previously discussed Methodists, Clarke did not believe in a gathering in or restoration of the Jews, or their mass conversion to Christianity, or their role in the final struggle against Antichrist. Instead, he suggested in his commentary on the New Testament, published in 1817, and his commentary on the Old Testament, published in 1825, that the role of Jews was simply to serve as a wretched and dispersed people, as perpetual monuments to the truth of Christianity. In his commentary on Matthew 24, he argued that the Jews, preserved as ‘a people scattered through all nations, … without temple, sacrifices, or political government’, reluctantly stand forth, despite their attempts to ‘suppress the truth’, as ‘unimpeachable collateral evidence’ of the predictions found in the New Testament. Reading the Gospel of Matthew as a prophetic text written before the sacking of Jerusalem, Clarke argued that ‘the destruction of Jerusalem’ had been foretold, and was a remarkable demonstration of ‘divine vengeance’ and a ‘signal manifestation of Christ’s power and glory’. Clarke concluded that, ‘thus has the prophecy of Christ been most literally and terribly fulfilled, on a people who are still preserved as continued monuments of the truth of our Lord’s prediction, and of the truth of the Christian religion’. Similarly, in his commentary on Jeremiah 15:4, he argued that the statement, ‘I will cause them to be removed into all kingdoms of the earth’, was in respect to ‘the succeeding state of the Jews in their different generations’. According to Clarke, ‘never was there a prophecy more literally fulfilled; and it is still a standing monument of Divine truth. Let infidelity cast its eyes on the scattered Jews whom it may meet with in every civilized nation of the world; and then let it deny the truth of this prophecy, if it can’. In his preface to the Epistle to the Romans, Clarke argued that the calamities endured by the Jews, and their continued survival as a distinct and separate people despite a ‘dispersion of about 1700 years, over all the face of the earth, everywhere in a state of ignominy and contempt’, was evidence of a ‘standing miracle’, and the extraordinary will and interposal of Heaven. According to Clarke, the continued presence of the Jews as a distinct but dispersed people, ‘for many ages, harassed, persecuted, butchered and distressed’ (by ‘Pagans and pretended Christians’), as ‘the most detestable of all people upon the face of the earth’, but nevertheless preserved, was in line with a prediction in the book of Jeremiah (‘for I will make a full end of all the nations whither I have driven thee: but I will not make a full end of thee, but correct thee in measure’ [Jeremiah 46:28]), that God will bring an end to other nations, but not the Jews. Clarke concluded, in a somewhat ontological vein, that ‘thus the very being of the Jews, in their present circumstances, is a standing public proof of the truth of Revelation’ [6]

Again, unlike the Methodist millenarians, Clarke did not prophesise the destruction of the Catholic Church or speculate with confidence as to the identity of Antichrist. Reflecting on the Antichrist in his commentary on Revelation 11:7 (‘and when they [the two witnesses] shall have finished their testimony, the beast that ascendeth out of the bottomless pit shall make war against them and shall overcome them, and kill them’), Clarke observed that the beast from the bottomless pit ‘may be what is called Antichrist’, but he concluded that other than some power opposed to ‘genuine Christianity’ and under ‘the influence and appointment of the devil’, it was impossible to say who or what Antichrist is. He noted that the conjectures about the identity of the beast (and the two witnesses) are manifold. As examples, he mentions as possibilities, ‘some Jewish power or person’, ‘one of the persecuting Heathen emperors’, and ‘the papal power’. Ultimately, the Antichrist (‘the beast’) remains an uncertain and shadowy figure in Clarke’s discourse. [7]

Portrait of Dr Adam Clarke, c. 1806, Methodist Archives /PLP 26/11/24

With his rejection of millenarian ideas, his limited interest in speculating about the identity of Antichrist, and his belief that Jews would be preserved in their dispersed, separate and wretched condition as perennial monuments to the truth of Christianity (rather than a gathering in of the Jews, and their embracing of Christianity), Clarke seems to have been an outlier compared to many of his Methodist colleagues from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However, whilst he seems to have been indifferent to the idea of a Catholic Antichrist, he did embrace other hostile myths and stereotypes about Catholics (as well as many hostile myths and stereotypes about Jews). Adam Clarke’s anti-Judaism and anti-Catholicism are examined in more detail in my article published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library: ‘“Monuments” to the truth of Christianity: Anti-Judaism in the Works of Adam Clarke’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, volume 93, issue 1, Spring 2017, 45-66 [link to journal volume] [link to author accepted manuscript]

References

[1] Norman Cohn, Europe’s Inner Demons: The Demonisation of Christians in Medieval Christendom (1975; repr., London: Pimlico, 2005), 23; and Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957; repr., London: Pimlico, 1993), 35.

[2] David Butler, Methodists and Papists: John Wesley and the Catholic Church in the Eighteenth Century (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1995), 129-134; and John Wesley’s Explanatory Notes upon the New Testament, notes on the Revelation 13:1 and 17:10-11, originally published in 1755, but the 12th edition has been used in this blog (New York: Carlton & Porter, no date), available online at archive.org, pages 650, 697-702, 714-715.

[3] The Unfinished letter from Charles Wesley to an unnamed correspondent, 25 April 1754, can be found in the John Rylands Special Collections, DDCW 1/51. For a transcript and discussion of this letter, see Kenneth G. C. Newport, ‘Charles Wesley’s Interpretation of Some Biblical Prophecies According to a Previously Unpublished Letter’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 77, no. 2 (1995), available online at Manchester eScholar, pages 31-52.

[4] Kenneth G. C. Newport, ‘Methodists and the Millennium: Eschatological Expectation and the Interpretation of Biblical Prophecy in Early British Methodism’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 78, no. 1 (1996), available online at Manchester eScholar, pages 103-122. For Joseph Sutcliffe, see pages 109-112. For Thomas Coke, see pages 121-122; and Joseph Sutcliffe, A Treatise on the Universal Spread of the Gospel, the Glorious Millenium, and the Second Coming of Christ (Doncaster: Gazette-Office, 1798).

[5] Thomas Taylor, Ten Sermons on the Millennium; or, The Glory of the Latter Days (Hull: G. Prince, 1789), sermon 1, ‘The Destruction of Antichrist’, pages 20-28.

[6] Adam Clarke, The New Testament, of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ; containing the text, taken from the most correct copies of the present authorised translation, including the marginal readings and parallel texts, with a commentary and critical notes. Designed as a help to a better understanding of the sacred writings, 3 volumes (London: J. Butterworth, 1817), commentary on Matthew 24:30-31 (and concluding notes for Matthew 24), and preface to commentary on Romans, page viii; and Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments. The text carefully printed from the most correct copies of the present authorized translation, including the marginal readings and parallel texts. With a commentary and critical notes, designed as a help to a better understanding of the sacred writings, 5 volumes (London: J. Butterworth, 1825), commentary on Jeremiah 15:4, 46:28.

[7] Clarke, The New Testament, of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, commentary on Revelation 11:7.

Twelfth EAJS Congress: “Branching Out. Diversity of Jewish Studies”

Twelfth EAJS Congress. “Branching Out. Diversity of Jewish Studies”. Frankfurt. July 2023.

“Jewish Studies” is a multi-disciplinary field that brings together scholars, topics and methods from across many academic disciplines. Additionally, Jewish Studies scholars are often involved in multi-disciplinary networks, cooperating and communicating with colleagues from a wide variety of fields. At the same time, research into Jewish history, culture, languages and the like is not limited to Jewish Studies departments, creating yet wider networks and even greater diversity. The twelfth EAJS congress, “Branching Out. Diversity of Jewish Studies”, taking place in Frankfurt/Main (Germany) on 16-20 July 2023, will showcase the diversity that is an integral part of Jewish Studies: research topics that range from the Bible and ancient history to contemporary Jewish thought and culture, a multitude of different sources from all over the world, methods and approaches from archaeology to digital humanities, and a vast array of interdisciplinary networks and research approaches. Scholars of Jewish Studies from Europe and beyond are invited to propose papers and sessions.

The following are links to various announcements for the 12th EAJS Congress:

Call for Papers (Abstracts/Sessions) – Deadline 31 December (23:59 GMT+1): https://www.eurojewishstudies.org/calls-for-papers/call-for-papers-twelfth-eajs-congress/

EAJS Emerge (forum for PhDs and emerging scholars) – Deadline 31 December (23:59 GMT+1): https://www.eurojewishstudies.org/calls-for-papers/twelfth-eajs-congress-16-20-july-2023-eajs-emerge-call-for-applications-deadline-31-december-2022/

Distinguished Panels for the Congress – Deadline 15 Jan 2023: https://www.eurojewishstudies.org/calls-for-papers/call-for-submissions-distinguished-eajs-panel-and-distinguished-eajs-graduate-student-panel-deadline-15-january-2023/

Horrors in Bucha and a barely-veiled call for cultural genocide

Russia’s retreat from the region surrounding Kyiv has revealed the fate of Ukrainian towns occupied by the Russian army. When the Ukrainian army re-entered Bucha on 1 April 2022, they discovered the Bucha Massacre. Bodies of murdered Ukrainian civilians, strewn in streets and alleys, with their hands tied behind their backs, mutilated, burnt and shot, were left by the Russian army to rot. There are also several accounts of torture and rape in Bucha, in some cases of young children. This, it would seem, is the reality of Putin’s vaunted “de-Nazification”.

Excavation of mass grave in Bucha. Photograph by Anastasia Taylor-Lind (link to Guardian article)

Significantly, just two days after the discoveries in Bucha, an article entitled “What should Russia do with Ukraine,” published by the Russian state-owned news agency RIA Novosti on 3 April 2022, called for the liquidation of the Ukrainian political, ethnic and cultural identity. Whilst stopping short of a call for Ukrainians to be killed en masse, the article did de-humanise Ukrainians in general as either “passive Nazis” or “active Nazis” (thereby making massacres like the one at Bucha more likely), and called for the suppression of Ukrainian “culture” and “education”, and the rejection of the Ukrainian “ethnic component of self-identification” (i.e. “de-Ukrainization”). The article even suggested that the very name, “Ukraine”, was to be eliminated. In other words, a barely-veiled call for “cultural genocide“, as originally conceived by Raphael Lemkin in 1944. Reports of Ukrainians being “evacuated” by the Russian army along corridors into Russia, “filtered” and shipped to camps in Siberia, deep within Russia and far away from Ukraine, reinforce this suspicion that Putin’s goal is not merely to seize Ukrainian territory (bad enough as that is), but rather to wipe away even the very idea of Ukraine (which in Putin’s mind is an existential obstacle to the re-birth of “Greater Russia”).

According to a translation of the article, provided by Ukraine Crisis Media Centre (UCMC), “Denazification is necessary when a significant part of the people – most likely the majority – has been mastered and drawn into the Nazi regime in its politics. That is when the hypothesis ‘the people are good – the government is bad’ does not work. Recognition of this fact is the basis of the policy of denazification.” The article stated that “the Nazis who took up arms should be destroyed to the maximum on the battlefield. There should be no significant differences between the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the so-called national battalions, as well as the territorial defence that joined these two types of military formations. All of them are equally involved in extreme cruelty against the civilian population, equally guilty of the genocide of the Russian people, and do not comply with the laws and customs of war. War criminals and active Nazis should be exemplarily and exponentially punished. There must be a total lustration. Any organizations that have associated themselves with the practice of Nazism [must be] liquidated and banned.” The article called for Ukraine’s leaders – which it referred to as “the Bandera elite” (an allusion to Stepan Bandera, a Nazi collaborator until the Gestapo arrested him because of his proclamation of the Ukrainian state, and an admittedly divisive character in Ukraine, seen by some as a freedom fighter who led an insurgency against the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s, and by others as a villain and violent antisemite; he was assassinated by the KGB in 1959) – to be “liquidated” as their “re-education is impossible”, and called for the “forced labour” of the “accomplices of the [Ukrainian] Nazi regime”. Chillingly, the article clearly had in mind the general population of Ukraine, as it explicitly stated that “Denazification is a set of measures in relation to the Nazified mass of the population.” The article explained that “in addition to the top, a significant part of the masses, which are passive Nazis, accomplices of Nazism, are also guilty. They supported and indulged Nazi power.” According to the article, “the just punishment of this part of the population is possible only as bearing the inevitable hardships of a just war against the Nazi system,” which, the article cynically concluded, was “waged as carefully and prudently as possible in relation to civilians.” “Further denazification of this mass of the population,” the article continued, would “consist in re-education, which is achieved by ideological repression (suppression) of Nazi attitudes and strict censorship: not only in the political sphere but also necessarily in the sphere of culture and education.” According to the article, “the terms of denazification can in no way be less than one generation, which must be born, grow up and reach maturity under the conditions of denazification.”

In a new twist that will likely serve to increase the genocidal language emanating from Moscow, Russian TV is now reframing the invasion of Ukraine as a religious or holy war. For example, on Friday 15 April 2022, Vyacheslav Nikonov, a member of Russia’s State Duma, drawing upon language found in religious apocalyptic discourse, suggested on “The Big Game,” a TV show on Channel One Russia, that the “holy war” against Ukraine was a clash between the armies of light on one side (i.e. Russia) and the forces of “absolute evil” on the other (i.e. Satan, the Antichrist, Ukraine and the United States). He stated that: “In the modern world, we are the embodiment of the forces of good. This is a metaphysical clash between the forces of good and evil… We’re on the side of good against absolute evil, represented by the Ukrainian nationalist battalions… and the American temple of Satan, located in Salem, expressed its support for Ukraine. This is truly a holy war, a holy war we’re waging and we must win” (reported and translated by Julia Davis in the Daily Beast on 18 April 2022). A couple of days prior to that, on Wednesday 13 April 2022, Nikonov had given in indication of forces that he believed would be added to the phalanx of evil aligned against Russia, referring to an as yet incomplete “Fourth Reich,” which would add Finland, Norway and Japan to its numbers (reported in Newsweek). According to Professor Christopher Partridge, a key element of apocalyptic discourse is that it persuades its audience (and authors) that they are participants in a great cosmic narrative, “that their lives have meaning, that their conduct matters, and that history has purpose … [that] their faith will be rewarded; goodness and truth will triumph; what currently threatens them as final evil will prove to have been interim evil.” (Christopher Partridge, The Re-Enchantment of the West, volume 2, 2005, p. 284). Some of this can be seen in statements by Andrei Kartapolov, another member of the State Durma, on The Evening With Vladimir Solovyov TV show on Friday 15 April. According to Kartapolov, “we’re entering a very interesting period in the development of modern history. We’re all incredibly lucky to be able to witness these great events.” He went on to state that “historians will later study this period, to talk about its role, its meaning as the turning point that determined the coming world order for many years to come. And we’re witnessing it first hand! More than that, we’re participating in it! We should be proud of that alone” (reported and translated by Julia Davis in the Daily Beast on 18 April 2022). And in a modern allusion to and refinement of the antisemitic blood libel myth, Sergey Mikheev, a Moscow propagandist, assigned the role of ritual murderer to Ukrainian Pagans and Western Satanists (rather than to the Jews as is traditional in such narratives). Mikheev stated on a Russian political talk show, The Evening With Vladimir Solovyov, that the “Ukrainian God” is “the Devil”, that the Ukrainian religion is Paganism, that it “demands human sacrifices,” “demands blood,” “killing and atrocities are the initiation, to plead loyalty to those dark powers,” and that Ukrainians crucify [Russian] soldiers. He also suggested that Ukraine itself was a blood sacrifice by the “Satanists” in the West, that Ukraine was being cut “as a pig at the sacrificial pagan altar,” as an offering to “those Gods they [i.e. the West] truly worship” (link to video, posted on Twitter, with translations by @JuliaDavisNews).

The dangers of the misappropriation of Holocaust history by Putin and his followers, their mythologizing of so-called “Ukrainian Nazism” and their “special operation” to “de-Nazify” Ukraine, increasingly framed in religious language, are starkly revealed in towns like Bucha and Borodyanka. None of this is to deny that Ukraine has its share of far-right groups – ironically, largely encouraged by the years of ongoing aggression emanating from Russia – but there is little evidence of these being any more prevalent than in many other democratic European countries including France and Germany (and considerably less than in Hungary, and, pointedly, Russia). As Jason Stanley – Professor of philosophy at Yale University and author of How Fascism Works (2018) – has pointed out, “Ukraine does have a far-right movement, and its armed defenders include the Azov battalion,” but “no democratic country is free of far-right nationalist groups, including the United States,” and in 2019, the Ukrainian far right received only 2% of the electoral vote, “far less support than far-right parties receive across western Europe, including inarguably democratic countries such as France and Germany” (Jason Stanley, “The Antisemitism Animating Putin’s Claim to ‘Denazify’ Ukraine”, The Guardian, 26 February 2022). It is worth noting that the Azov regiment, which was formed out of the original far-right Azov battalion, is a tiny component of the Ukrainian military (approximately 1,000 soldiers), and is not the same unit as existed back in 2014-15, with the far-right elements today being significantly less prevalent (though admittedly not entirely gone), and with it’s recruitment being open more broadly to Ukrainian society (link to video report by Ros Atkins, BBC, posted on Twitter, 24 March 2022).

If the West wants to put a stop to this false “de-Nazification” – which is to say, Russia’s campaign to turn Ukrainian towns and cities into rubble, and to liquidate the very idea of Ukraine – then it needs to do more to help Ukraine. Significantly, according to the article in RIA Novosti, the “collective West” is “the designer, source, and sponsor of Ukrainian Nazism”, which probably suggests that RIA Novosti, and possibly Putin himself, would like to see a similar Russian campaign of so-called “de-Nazification” inflicted upon the countries and populations of the so-called “totalitarian” West. And according to State Duma deputy, Oleg Morozov, on a TV show on Thursday 14 April 2022, “Today’s world is very dangerous for us, but it’s also dangerous for Americans, for the Chinese, for the Europeans, for the Polish, and first and foremost, for the Baltics. Let them remember that denazification is a long, endless process and will very likely not end with Ukraine” (reported and translated by Julia Davis in the Daily Beast on 18 April 2022). Making sure that Ukraine defeats Russia’s invasion and attempted cultural genocide may therefore not just be the moral thing to do, it may also be in the enlightened self-interest of the West.

[Blog post updated 19/04/2022]

Link for other blog posts on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022)

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Like most right-minded people, I am horrified by the barbaric and immoral invasion of Ukraine by Putin’s regime. It is not clear what rational endgame Putin could possibly have in mind. He has brought devastation to Ukraine and its people, and is bringing economic catastrophe to his own country. The brazenness of the lies that Putin tells the world to try to justify his invasion is staggering. He falsely claims that his goal is to “de-nazify” Ukraine, and he refers to the Ukrainian leadership as “drug addicts” and “neo-Nazis”. Volodymyr Zelensky, the democratically-elected President of Ukraine, is neither a corrupt drug addict nor a neo-Nazi, but rather a brave wartime leader (when offered an evacuation by the US, he replied, “the fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride”). He is also Jewish. Zelensky lost several relatives to the Holocaust. Additionally, from 2016-2019, Ukraine had a Jewish Prime Minister (Volodymyr Groysman) as well, making it, to the best of my knowledge, the only European country to have simultaneously had a Jewish President and Prime Minister. Putin’s lies and warped claims, casting Jews and Ukrainians as a cabal of corrupt gangsters and Nazis, and Russians as their victims, are an inversion of reality and a misappropriation of Holocaust history. And, as if to ram Putin’s lies and hypocrisy home, Russian missiles have struck the Holocaust memorial at Babyn Yar, the site where tens of thousands of Jews and other victims of the Holocaust were murdered, by Nazis, during the Second World War.

None of this is to deny that Ukraine has its share of far-right groups – ironically, largely encouraged by the years of ongoing aggression emanating from Russia – but there is little evidence of these being any more prevalent than in many other democratic European countries including France and Germany (and considerably less than in Hungary, and, pointedly, Russia). As Jason Stanley – Professor of philosophy at Yale University and author of How Fascism Works (2018) – has pointed out, “Ukraine does have a far-right movement, and its armed defenders include the Azov battalion,” but “no democratic country is free of far-right nationalist groups, including the United States,” and in 2019, the Ukrainian far right received only 2% of the electoral vote, “far less support than far-right parties receive across western Europe, including inarguably democratic countries such as France and Germany” (Jason Stanley, “The Antisemitism Animating Putin’s Claim to ‘Denazify’ Ukraine”, The Guardian, 26 February 2022). It is worth noting that the Azov regiment, which was formed out of the original far-right Azov battalion, is a tiny component of the Ukrainian military (approximately 1,000 soldiers), and is not the same unit as existed back in 2014-15, with the far-right elements today being significantly less prevalent (though admittedly not entirely gone), and with it’s recruitment being open more broadly to Ukrainian society (link to video report by Ros Atkins, BBC, posted on Twitter, 24 March 2022).

Whilst I am relieved that the UK, EU and US have put in place several measures to support Ukraine and the Ukrainian people, and to sanction and condemn Putin and his inner circle of close supporters, these can, and should, go much further. The UK government should do more to welcome Ukrainian refugees escaping the carnage being inflicted on their country (for example, by easing or waiving the visa requirements and reducing the red tape). Following the lead of Germany and France, the UK should start to actually seize the mega-yachts, properties and money of Russian oligarchs, rather than just talking about doing so. And those seized resources should be quickly liquidated and the proceeds used to help Ukrainians as soon as possible. Sanctions applied by the UK should become active immediately, without allowing Putin’s supporters several weeks or months to move and re-launder their money (the UK needs to act faster before Russian assets are spirited away). Europe need to do more to break its dependence on Russian gas (and oil). And the UK and US need to remember that whilst Ukraine might not be a member of NATO, the UK and US made commitments, as signatories to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, to protect the sovereignty and integrity of Ukraine (in return for which, Ukraine gave up its significant stockpile of nuclear weapons).

[Blog post updated 19/04/2022]

Link for other blog posts on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022)

Cecil Roth, Arthur Day and the Mortara Affair (1928-1930)

In June 1929, Father Arthur Day, an English Jesuit, the Vice-President of the Catholic Guild of Israel, and author of several booklets and articles on converting the Jews, published an article on the Mortara Affair in The Month (the periodical of the English Jesuits): Arthur F. Day, “The Mortara Case,” Month, CLIII (June 1929): 500-509.

The Mortara Affair was an incident in which a six year old Jewish child, Edgardo Mortara, was forcibly removed from his family in 1858 by the Carabinieri (the military police of the Papal States), placed in the care of the Church, and later adopted by Pius IX. This was because a Catholic maid (Anna Morisi), afraid that Edgardo was about to die, illicitly baptised him – or at least claimed to have done so. Years later she revealed this to Father Feletti, the inquisitor in Bologna. The matter was referred to the Holy Office, which declared that the baptism was valid, and that according to papal law the boy must thus be removed from his family and brought to the House of the Catechumens in Rome. He was raised as a Roman Catholic and later became a Catholic priest. For a detailed examination of the Mortara Affair as it unfolded in the 1850s, see the following excellent book by Professor David Kertzer: The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara. For responses to the abduction in the English Catholic Tablet newspaper at the time, please see my blog post entitled “The Tablet and the Mortara Affair (1858)”.

Incidentally, there are plans to adapt Kertzer’s book into a movie directed by Steven Spielberg [link]. This has spurred the publication of an English translation of the until recently unpublished memoirs of Edgardo Mortara with an introduction by Vittorio Messori defending Pius IX’s abduction of the young Jewish child [link], as well a series of online review articles and responses by those who support (e.g. Romanus Cessario in First Things) or abhor this defence of Pius IX (e.g. Robert T. Miller in Public Discourse). [See also Armin Rosen in Tablet Magazine for a brief survey of the recent responses].

.

Representation of the abduction by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882). See Maya Benton’s article (link)

.

Returning to the subject in hand, Father Day wrote his article about the Mortara Affair after a heated altercation on the subject of forced baptisms with the prominent Anglo-Jewish scholar, Cecil Roth, in the pages of the Jewish Guardian. Cecil Roth had presented a lecture at the Jewish Historical Society of England in December 1928 on “the Last Phase in Spain.” According to the Jewish Chronicle, Roth discussed the persecution of Jews in Spain at the end of the fourteenth century, the institution of the Spanish Inquisition, and the expulsion from Spain in 1492. Roth explained that a series of massacres in 1391 sapped the will of the Jews in Spain, and that “the number of those killed in these massacres was as nothing compared with the number of those who submitted to mass conversion in order to save their lives.” “Jewish History in Spain,” Jewish Chronicle, 14 December 1928, 10.

Father Day attended Roth’s lecture and a heated debate apparently ensued between them on the subject of forced baptisms (according to the Jewish Guardian, Day raised objections to Roth’s “historiography”; Day denied this, stating that he was not “conscious of having objected to the lecturer’s ‘historiography,'” but rather simply asked Roth a “few questions” which “resulted in a friendly argument”). “Dr. Cecil Roth and Father Day,” Jewish Guardian, 28 December 1928, 12, and Letter from Arthur F. Day to the Editor, dated 31 December 1928, Jewish Guardian, 4 January 1929, 4.

Jewish Guardian: 28 December 1928, p.12 and 4 January 1929, p.4.

After the lecture, Day wrote a letter to Cecil Roth, dated 13 December 1928. His letter explained that whilst under normal circumstances (“cases less urgent”), the permission of the parents must be obtained before baptising Jewish children, in the exceptional circumstance in which “an unbaptized person is in danger of death, baptism, which we regard as of primary importance for salvation, should, if possible, be conferred.” Day argued that the Mortara family had “broken the law in having a Catholic servant in their household, and so to some extent they brought the trouble on themselves.” He also invoked a traditional anti-Masonic narrative, claiming that the opposition to Mortara’s removal from his parents was “to a great extent of the anti-Popery and Continental freemason type.” Cecil Roth subsequently published Father Day’s letter (without first asking Day’s permission) in the Jewish Guardian. Letter from Arthur F. Day to Cecil Roth, dated 13 December 1928, Jewish Guardian, 28 December 1928, 12.

After Roth published Father Day’s letter, Day in turn published the rest of the correspondence between them (two letters from Day, dated 21 December and 26 December 1928, and two letters from Roth, dated 23 December and 28 December 1928) in the next issue of the Jewish Guardian. See “Dr. Roth and Father Day: Further Correspondence on the Mortara Case,” Jewish Guardian, 4 January 1929, 4. See also Letter from Arthur F. Day to the Editor, dated 14 January 1929, Jewish Guardian, 18 January 1929, 9.

Roth was not impressed by Day’s arguments. In a letter dated 19 December 1928, he noted that the young Mortara was only two or three years of age at the time he was baptized, and that the “ceremony of baptism was a merest travesty, having been performed with ordinary water and by an uneducated servant girl.” In a letter dated 23 December, he stated that he had “no desire nor intention to protract correspondence upon an episode the facts of which are quite clear. Those who, like myself, respect the noble traditions of the Catholic Church can only look forward to the day when this outrage upon humanity will be buried in oblivion.” Whilst Father Day was eager to keep the conversation alive, Roth correctly observed that Day distorted the facts, and that there was therefore little to be gained in continuing the correspondence. After writing his own short essay on the history of forced baptisms and the Mortara Affair, published on 11 January 1929, Roth concluded with the following statement: “I have no intention to protract the correspondence upon this question between myself and Father Day. But it may be noticed en passant that there are curious discrepancies between the singularly unconvincing facts which he cites in the name of the Jewish Encyclopedia and what is to be found in the ordinary editions of that work.” Letter from Cecil Roth to Arthur Day, dated 19 December 1928, Jewish Guardian, 28 December 1928, 12; Letter from Cecil Roth to Arthur Day, dated 23 December 1928, Jewish Guardian, 4 January 1929, 4; Cecil Roth, “Forced Baptisms: A Chapter of Persecution,” Jewish Guardian, 11 January 1929, page 7 and page 8.

Jewish Guardian, 11 January 1929, pp.7-8.

Day subsequently published his article defending the Mortara abduction in The Month in June 1929, informing his readers that it should not be “impossible for Jews to realize the importance we attach to baptism seeing that they, if at all orthodox, regard circumcision as a religious ordinance of the very first rank.” He rejected Roth’s argument that the baptism was a “ridiculous travesty,” noting that “it should occur to anyone at all experienced in historical research that the Sacred Congregation of the Inquisition is a fairly competent body which may be trusted to decide whether a clinical baptism has been correctly performed.” The crux of Day’s argument was that “if an infant is in serious danger of death, theologians teach that it should be baptised even without the consent of the parents.” He clarified that this “apparent overriding of parental rights” was explained and justified by the Catholic belief that “under such circumstances this sacrament is of eternal importance to the child, and to withhold it, when there is the opportunity of bestowing it, would be a violation of the law of charity.” According to Day, it is laid down as a “general rule” that in the instances where this occurs with “Hebrew infants,” with the child having been “validly” even if “illicitly” baptised, then they must be “separated from their relations and educated in the Christian faith. The parents, even though they may make promises, cannot be trusted in such a matter to fulfil them. The injury done to them is not so great as that which would be done to the dying child if the sacrament which opens heaven were withheld.” Father Day observed that “Dr. Cecil Roth persisted in inveighing against the inhumanity of the papal procedure and refused to consider what we might call for the moment, in deference to his view, the extenuating circumstances.” He described his “duel” with Cecil Roth as a “useful object-lesson regarding Jewish mentality when confronted by the Catholic claim.” As he had in his letter dated 13 December 1928, he suggested that the Mortara outcry and agitation was “set on foot” by “Protestants”, “Freemasons” and the “riffraff of the revolutionary parties.” Arthur F. Day, “The Mortara Case,” Month, CLIII (June 1929): 500-509.

On 18 September 1929, Arthur day visited the nearly 80-year old Edgardo Mortara (by then Father Mortara, a member of the Canons Regular of the Lateran) at his “monastic home” just outside Liège. In 1930, he appended an account of this visit to the article he had written for The Month. This was published as a 28-page Catholic Guild of Israel booklet by the Catholic Truth Society. In this, Arthur Day observed that Father Mortara’s “buoyant and enthusiastic temperament is so prone to exult at the memory of the great deliverance and the many graces and favours that followed it, that it is not easy to get from him the sort of information that is dear to reporters. He is so full of fervour and fire that it is difficult for him to adapt himself to a matter-of-fact enquirer. Nobody could be more obliging: his Prior said to me of him, using a French proverb: ‘If it could give pleasure to anyone he would gladly be cut into four.'” Arthur Day recorded that Father Mortara told him that he became a member of his religious order early in his life because he felt that “God has given me such great graces; I must belong entirely to him.” A. F. Day, The Mortara Mystery (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1930), 17-19. He also wrote to Cecil Roth to present him with a copy of the booklet, and he noted at the end of the booklet that “it is pleasant to record that Dr. Roth … acknowledged the receipt of a copy in a kindly and friendly tone.” Letter from A. F. Day to Dr Roth, “Cecil Roth Letters,” 19 June 1930, held in Special Collections, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, File 26220; A. F. Day, The Mortara Mystery, 28.

In 1936, Cecil Roth published a book presenting a short history of the Jewish people. In this book, he mentioned in passing the Mortara Affair. He stated that in 1858, a “wave of indignation swept through Europe by reason of the kidnapping at Bologna (still under Papal rule) of a six-year-old Jewish child, Edgardo Mortara, on the pretext that he had been submitted to some sort of baptismal ceremony by a servant-girl four years previous.” In May 1936, Father Day was reported (in the Catholic Herald) as saying that “there is undeniably much anti-Christian and still more anti-Catholic bigotry among the London Jews.” He probably had Cecil Roth’s comments about the Mortara Affair in mind when he added that “in spite of appalling ignorance, they pose as competent critics of Catholic theology. The puerility of it passes comprehension; and yet it is among the intelligentsia that one finds the worst offenders.” A few weeks later, on 2 June 1936, Father Day wrote to Cecil Roth about his short history of the Jewish people, stating that he “found much to admire, but also some portions distinctly less admirable.” Unsurprisingly, the portions that Day found “less admirable” were those relating to the Mortara Affair. Day argued that “‘kidnapping’ is not the right word” because “at that time and in that place it was a legal act.” He also stated that the baptism performed by the young Catholic maid was “a valid clinical baptism” and “not a pretext.” It was, he suggested, not merely a pretext for abduction but a genuine reason. Cecil Roth must have replied to Day (letter not found), because Father Day sent him another letter on 10 June 1936, thanking him for acknowledging his letter. In this second letter, Day suggested that it was not a kidnapping because “the Oxford Dictionary … defines ‘kidnapping’ as ‘carrying off a child by illegal force'” (the emphasis by underlining was Father Day’s). Day concluded that “if a modern incident can be so maltreated, what about the poor old Middle Ages!” See Cecil Roth, A Short History of the Jewish People (London: Macmillan and Company, 1936), 378; “Jews and Christians: A Priest’s Experience,” Catholic Herald, 15 May 1936, 2; Letters from A. F. Day to Dr Roth, “Cecil Roth Letters,” 2 June 1936 (with attached note) and 10 June 1936, held in Special Collections, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, File 26220.

In 1953, Cecil Roth returned to the Mortara Affair. He noted that “Modern apologists endeavoured to justify what occurred by calling attention to the breach of the law committed by the Mortara family in having a Christian servant in their employment at all, and by pointing out that on the capture of Rome twelve years later, after having been sedulously kept away from all Jewish influence during the most impressionable years of his life, Edgardo Mortara neglected the opportunity to return to his ancestral faith.” Roth referred to the controversy with Father Day which began in 1928, observing that Day later wrote to him in response to his A Short History of the Jewish People (i.e. Day’s letter of 2 June 1936), “indignantly protesting against my statement that Edgardo Mortara was ‘kidnapped.'” Roth was understandably surprised and frustrated that Father Day believed it was in any sense a creditable defence of the kidnapping that the six-year-old Edgardo Mortara, as a result of being illicitly baptised as a baby by a servant girl, had been “removed from his parents’ custody by process of the law!” Cecil Roth, Personalities and Events in Jewish History (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1953), 273-274.

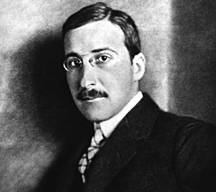

Stefan Zweig’s Struggle with Nietzsche and the Daimonic Spirit

Stefan Zweig was a prolific Austrian author of novels, short stories, plays and biographies. He was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna in November 1881 and committed suicide in Petrópolis, Brazil, in February 1942.

.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942)

.

Zweig developed a fascination with Friedrich Nietzsche when he was a student at the Maximilian gymnasium (school) in Vienna. According to Zweig’s autobiography, The World of Yesterday, and his examination of Nietzsche in Der Kampf mit dem Dämon (The Struggle with the Daemon), the gymnasium provided a “treadmill” of learning which was designed to suppress the exuberant spirit of youth. Zweig cast about for solace and found it in Nietzsche’s books. These he discussed at coffee houses and read under the desk as his teacher “delivered his time-worn lecture.” It was the rebellious nature of Nietzsche that attracted Zweig. According to Zweig, Nietzsche chose to “kick over the traces of his official duties and, with a sigh of relief, quit the chair of philology at Basel University.” Having broken the “shackles which bound him to the past” he was ready to become “an outlaw, an amoralist, a sceptic, a poet, a musician.” Ironically the gymnasium’s oppressive regime provided the fertile environment necessary for Nietzsche’s influence to take hold of Zweig, and consequently he developed a “hatred for all authority” and a “passion to be free – vehement to a degree” that was, according to Zweig, “scarcely known to present-day youth.”

.

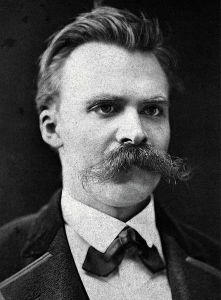

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

.

The aspect of Nietzsche that appealed most to Zweig was his so-called “Dionysian” spirit. Zweig’s examination of Nietzsche in The Struggle with the Daemon was, as he acknowledged, not so much a biography as a portrait of a life as “a tragedy of the spirit, as a work of dramatic art.” It was “the fact that his daimonic nature was given free reign,” despite the inherent self destructive risk, that appealed to Zweig. This he felt transformed Nietzsche’s destiny into “legendary wonder.” Zweig repeatedly contrasted Nietzsche with Goethe. He suggested that Goethe also had a daimonic spirit, but that he recognised it and kept it under tight control, so that he could “be the ruler of his own destiny.” According to Zweig, as a rule “the thralls of the daimon were torn to pieces,” but Goethe opposed or subdued the “Dionysian disposition,” and “having subdued the daimon, was self-controlled to the end.” For Zweig this made Goethe a less interesting character than Nietzsche. However, in placing the unrestrained Dionysian spirit on a pedestal, Zweig ignored a critical aspect of Nietzsche’s own philosophy. Nietzsche developed a complex vision of two contrasting human drives. According to Nietzsche, the “Apollonian” exemplified the principle of individuation; the distinct, well ordered, disciplined, coldly logical, restrained and carefully bounded nature of individual existence. Conversely, the “Dionysian” exemplified the collapse of the principle of individuation: passion, intoxication, ecstasy, primal savagery and the dissolution of the boundaries that keep the individual distinct from nature. Whilst Nietzsche regarded neither the Apollonian nor Dionysian drives as healthy in isolation, he did emphasise the Dionysian spirit as the key to cultural regeneration in The Birth of Tragedy. However, Nietzsche later warned that this Dionysian spirit, though crucially important, should be tempered by the Apollonian.

Despite Zweig’s admiration of the Dionysian spirit, his portrait of Nietzsche was not without a measure of equivocation. He suggested in The Struggle with the Daemon that Nietzsche (along with Hölderlin and Kleist) was a thrall, “possessed … by a higher power, the daimonic.” This daimonic nature impelled him “towards danger, immoderation, ecstasy, renunciation, and even self-destruction.” He argued that this spirit enabled his mind to reach new heights but that ultimately it destroyed him. While Zweig admired Nietzsche’s spirit he also recognised the surface reality of his life. Nietzsche worshiped amor fati, happiness and good health. Yet as Zweig showed, the reality was that he was also a lonely man, constantly ill, reliant on tinctures and medicaments, unhappy and timid in his everyday dealings with other people.

Despite this equivocation, Zweig’s life would suggest that he did more than pay lip service to Nietzsche’s Dionysian ideal. He glorified composers, poets and writers, infused his own prolific works with his emotional life, and deployed his art as his primary response to the suffering and catastrophes of his time. Zweig informs us that “Nietzsche wished neither to better the world nor to inform the world.” “His ecstasy was,” Zweig suggested, “an end in itself, a delight sufficient in itself, a personal voluptuousness, wholly egoistical and elementary.” Zweig likewise privileged the artistic spirit as a superior end in itself over active worldly participation. He regarded Erasmus of Rotterdam as an example of the anti-fanatical life par excellence, a man to whom “artistic achievement and inner peace is the most important thing on earth.” He suggested that Jews should refrain from pursuing political goals and solutions which only draw attention and increase antisemitism, and instead follow the example of Erasmus. This, Zweig suggested, was his “own way of life symbolized.”

Zweig had always been a pacifist. During the First World War he felt that his pacifism demanded that he use his pen in solidarity with the innocent victims of the conflict. Consequently he worked with Romain Rolland and other literary figures to develop a peace campaign in Switzerland. However, by the time the Nazis rose to power, his pacifism had warped into a paralyzing passivity. Such was his interpretation of Erasmus’s way of life. This probably explains why Zweig refused requests from his friends during the early 1930s to write anything against fascism and Nazism. Referring to an operatic project he had collaborated on with Richard Strauss (Zweig wrote the libretto for Die schweigsame Frau), he observed in The World of Yesterday that “from all quarters friends urged me to protest publicly against a performance in National Socialist Germany.” He refused to protest, stating that he “fundamentally” loathed “public and pathetic gestures.” According to one of his biographers, Donald Prater, when Zweig was encouraged by his friend Ernst Fischer to write an article against fascism, he felt unable to comply, feeling that it was the author’s duty in such times to publish only things that were “inspiring and satisfying.”

Zweig’s failure to deploy his pen against fascism and antisemitism can be contrasted with Nietzsche. Nietzsche was ambivalent if not hostile about Judaism and Christianity as cultural systems (he regarded both as forms of slave morality), but he praised and defended Jews qua Jews. For example, in Beyond Good and Evil (§251), he described Jews as “the strongest, toughest, and purest people now living in Europe; they know how to prevail even under the worst conditions,” and he envisaged an important role for Jews in the regeneration of European culture. He stated that “to that end it might be useful and fair to expel the anti-Semitic screamers from the country.” Nietzsche expressed similar sentiments in Human, All-Too-Human (§475) and Daybreak (§205). In a letter to his sister around Christmas 1887, Nietzsche stated that he was filled with “ire or melancholy” over her marriage to “an anti-Semitic chief.” He even stated in a letter to Franz Overbeck in January 1889, shortly after the beginning of his psychological breakdown, that he was having all “anti-Semites shot”.

Zweig’s Dionysian ideal had a dark side. According to Friderike Zweig (Friderike was Stefan’s first wife and his close friend even after he remarried), he was “interested in mediocre, stupid or luke-warm people only if they were suffering.” Friderike observed that he depicted “illiterates as mental cripples, unable to grasp the breadth of the universe,” and considered “average people as a ‘quantité négligeable’”. According to Friderike, in this respect, he “contradicted his otherwise humane approach” (in Friderike Zweig’s biography: Stefan Zweig). Something of this can be seen in Erasmus, in which Stefan blamed the “broad masses of the people” for preventing his hero’s “lofty and humane ideals of spiritual understanding” from coming to fruition. The “average man,” he concluded, was too far “under the spell of hatred, which demands its rights to the detriment of loving-kindness.”

Zweig’s air of superiority over the “average” or “illiterate” man can also be found in his Schachnovelle (1942; published as The Royal Game in 1944 and subsequently as Chess or Chess Story). In this novella, Czentovic, an almost unbeatable chess playing prodigy, is depicted as the antithesis of Zweig’s Dionysian ideal. Czentovic is portrayed as a “half-illiterate” simpleton, “indolent,” “slow-speaking,” “narrow-minded,” with a “vulgar greed,” ignorant “in every field of culture,” unable “to write a single sentence in any language without misspelling a word,” and completely lacking in “imaginative power.” However, eminent intellectuals who were “his superior in brains, imagination, and audacity” all collapsed before his “tough, cold logic.” This depiction of the one dimensional simpleton, a pure Apollonian with no Dionysian spirit, stands in contrast to the tragic culture loving “Dr B.” Dr B is presented as having suffered a prolonged isolation at the hands of the Nazis resulting in a psychological breakdown. Whether consciously or unconsciously, this was clearly based upon Zweig’s perception of his own experience of isolation in Brazil. Dr B, now free from his isolation in the hotel room, challenges and at first manages to defeat the chess prodigy, but Czentovic adapts to his new opponent. Recognizing Dr B’s psychological fragility, he adopts an infuriating slow pace in order to break him. In the rematch, Dr B is not only defeated but driven to the brink of madness by Czentovic’s relentless but snail paced logic. Dr B’s Dionysian spirit is crushed by the cold Apollonian logic and brutal psychology of his supposedly inferior opponent.

Zweig’s so-called “humane approach,” which privileged those with an artistic spirit over the “illiterate” and “average” person, had more than a passing resemblance to Nietzsche’s portrayal of “noble” benevolence. In On the Genealogy of Morals (bk I, §10-11), Nietzsche expressed admiration for the “nobility” who employ “benevolent nuances” in their dealings with the so-called “lower orders”. According to Nietzsche, these lower orders are driven by the “venomous eye of ressentiment.” Zweig similarly suggested that the “average man” was “under the spell of hatred.” Conversely, they both believed that the so-called noble man, with his Dionysian artistic spirit, is able to consider those unlike him with a benign forbearance, as merely “bad” rather than “evil.” Zweig’s intoxication with freedom, his consistent dissolution of the boundaries between art and life, and his compassionate but disdainfully patronising attitude towards so-called “average” people, does seem to fit with Nietzsche’s Dionysian ideal, though crucially he ignored Nietzsche’s later observation that it was dangerous not to temper it with Apollonian self control.

Jacob Golomb argued in “Stefan Zweig: The Jewish Tragedy of a Nietzschean ‘Free Spirit’” that Zweig’s suicide was the result of “his indefatigable determination to subsist all his life as a ‘pure’ Nietzschean.” Golomb observes that “speaking of Nietzsche’s aversion to pity, Zweig continues to refer to him as to ‘the most brilliant man of the last century.’” However, Zweig in fact developed an ambivalent rather than purist attitude towards Nietzsche. The short extract, “the most brilliant man of the last century,” is found in his novel Beware of Pity (1939). The full passage from this novel reveals an abhorrence to Nietzsche’s aversion to pity rather than, as Golomb implies, a sympathy for it: “But you’ll never get me to utter the word ‘incurable.’ Never! I know that it is to the most brilliant man of the last century, Nietzsche, that we owe the horrible aphorism: a doctor should never try to cure the incurable. But that is about the most fallacious proposition of all the paradoxical and dangerous propositions he propounded. The exact opposite is the truth.” Unlike Dr. Condor, the character in the novel that articulates this sentiment, Zweig did not have the emotional resources to attempt to cure the incurable. This does not demonstrate, as Golomb suggests, the “bankruptcy of the existential stance of a Jewish ‘free spirit’” – but simply that Stefan Zweig lacked, like many other people of his time, the resilience necessary to deal with the catastrophe occurring in Europe. One reason for this weakness was the emotional scars he carried from the First World War. One moment Europe had been in a golden age of progress and the next it was falling apart. Zweig’s previously unflinching faith in a supra-national Europe crumbled as a consequence.

In Schachnovelle, Zweig contrasted Dr B’s isolation, forced by the Nazis to remain in a comfortable but plain hotel room for months at end with only a clandestinely hidden book of chess solutions to entertain him, with that of Jews who suffered physically in concentration camps. This comparison (in which he suggested that Dr B’s fate was worse) would seem to reveal Zweig’s inability to truly confront or understand the horrors that Jews were facing in Europe during the early 1940s. However, when Zweig wrote this novella, he, like Dr B, was on the brink of a psychological break. Shortly thereafter he committed suicide (and the novella was published posthumously). His alter-ego, Dr B, surmised that the Jews in the concentration camps at least “have seen faces, would have had space, a tree, a star, something, anything, to stare at, while here everything stood before one unchangeably the same, always the same, maddeningly the same.” Like Dr B, Zweig was unable to cope with his sense of isolation. Zweig managed to escape the Nazi plague spreading across Europe and ended up in Brazil in August 1940 (two years prior to the publication of Schachnovelle). According to Friderike Zweig (by this point Stefan’s ex-wife), he wrote to her to inform her that “the landscape was indescribably beautiful, the people charming, Europe and the war more remote.” He stated that “with a good library, life here could be very pleasant.” He expressed a similar sentiment in Brazil: A Land of the Future. According to Zweig, “the European arrogance which I had brought with me as so much superfluous luggage vanished with astonishing rapidity. I knew I had looked into the future of our world.” However, the “fairy-like Petrópolis” provided only a temporary respite. He felt guilt about the fate of the Jews he had left behind. He also felt a crushing sense of isolation. His attempts to overcome these feelings through his usual solution, the creation of uplifting literary works, failed. Like Nietzsche, Zweig was ultimately torn to pieces by his struggle with the Daemon. When he could endure these feelings no longer, he committed suicide.

New Publication: ‘Anti-Judaism in the Works of Adam Clarke’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library.

New research article in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 93:1 (Manchester University Press, Spring 2017): ‘”Monuments” to the Truth of Christianity: Anti-Judaism in the Works of Adam Clarke’.

Abstract: The prevailing historiographies of Jewish life in England suggest that religious representations of ‘the Jews’ in the early modern period were confined to the margins and fringes of society by the ‘desacralization’ of English life. Such representations are mostly neglected in the scholarly literature for the latter half of the long eighteenth century, and English Methodist texts in particular have received little attention. This research article addresses these lacunae by examining the discourse of Adam Clarke (1760/2–1832), an erudite Bible scholar, theologian, preacher and author and a prominent, respected, Methodist scholar. Significantly, the more overt demonological representations were either absent from Clarke’s discourse, or only appeared on a few occasions, and were vague as to who or what was signified. However, Clarke portrayed biblical Jews as ‘perfidious’, ‘cruel’, ‘murderous’, ‘an accursed seed, of an accursed breed’ and ‘radically and totally evil’. He also commented on contemporary Jews (and Catholics), maintaining that they were foolish, proud, uncharitable, intolerant and blasphemous. He argued that in their eternal, wretched, dispersed condition, the Jews demonstrated the veracity of biblical prophecy, and served an essential purpose as living monuments to the truth of Christianity.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.93.1.3

Publication date: March 1, 2017

For more information, please see:

Link to author accepted manuscript

Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies. ‘Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism’. Volume 12.

This volume attempts to make a modest contribution to the historical study of Jewish doubt, focusing on the encounter between atheistic and sceptical modes of thought and the religion of Judaism. Along with related philosophies including philosophical materialism and scientific naturalism, atheism and scepticism are amongst the most influential intellectual trends in Western thought and society. As such, they represent too important a phenomenon to ignore in any study of religion that seeks to locate the latter within the modern world. For scholars of Judaism and the Jewish people, the issue is even more pressing in that for Jews, famously, the categories of religion and ethnicity blur so that it makes sense to speak of non-Jewish Jews many of whom have historically been indifferent or even hostile to religion.

Themed volume: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism.

Editor: Daniel R. Langton.

Assistant editor: Simon Mayers.

Open Access, freely available online: www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html

Contents:

- Introduction.

- Kenneth Seeskin, From Monotheism to Scepticism and Back Again.

- Joshua Moss, Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism.

- David Ruderman, Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present.

- Benjamin Williams, Doubting Abraham doubting God: The Call of Abraham in the Or ha-Sekhel.

- Károly Dániel Dobos, Shimi the Sceptical: Sceptical Voices. in an Early Modern Jewish, Anti-Christian Polemical Drama by Matityahu Nissim Terni.

- Jeremy Fogel, Scepticism of Scepticism: On Mendelssohn’s Philosophy of Common Sense.

- Michael Miller, Kaplan and Wittgenstein: Atheism, Phenomenology and the use of language.

- Federico Dal Bo, Textualism and Scepticism: Post-modern Philosophy and the Theology of Text.

- Norman Solomon, The Attenuation of God in Modern Jewish Thought.

- Melissa Raphael, Idoloclasm: The First Task of Second Wave Liberal Jewish Feminism.

- Daniel R. Langton, Joseph Krauskopf’s Evolution and Judaism: One Reform Rabbi’s Response to Scepticism and Materialism in Nineteenth-century North America.

- Avner Dinur, Secular Theology as a Challenge for Jewish Atheists.

- Khayke Beruriah Wiegand, “Why the Geese Shrieked”: Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Work between Mysticism and Sceptics.

Melilah is published electronically by the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Manchester (ISSN 1759-1953), and as a printed edition by Gorgias Press.

The Anti-Antisemitism and Anti-Fascism of the Catholic Worker, 1935-1938

The English Catholic Worker (inspired by, but not to be confused with the longer-lived American newspaper of the same name), which was founded in June 1935 as the aptly named newspaper of the English branch of the Catholic Worker movement, provides a significant contrast to the other English Catholic newspapers of the time (such as the Catholic Herald and the Catholic Times). It was the only newspaper to focus primarily on representing the poorer working-class Catholics of England, addressing issues such as a just wage, workers’ rights, working conditions, and trade unions. It had a significant circulation of about 32,000 copies per issue during 1937, rivalling that of the Catholic Times, though falling short of the better-selling Catholic Herald (which had a circulation approaching 100,000 readers by 1936). Unlike the American Catholic Worker (which is still running), the English Catholic Worker ceased publication in 1959. For an account of the English Catholic Worker’s first year of existence, see Barbara Wall, “The English Catholic Worker: Early Days,” Chesterton Review, August 1984. For a discussion of the English Catholic Worker‘s discourse about Jews and antisemitism from 1939 to 1948, see Olivier Rota, “The ‘Jewish Question’ and the English Catholic Worker, 1939–1948,” Houston Catholic Worker, May-June 2005 [My thanks to Louise Zwick at the Houston Catholic Worker for providing me with the text for Olivier Rota’s article.].

During the 1930s, the Catholic Herald expressed ambivalence and at times sympathy for fascism and antisemitism, antipathy for liberalism (which it blamed for “destroying utterly the organic character of the western European States”), and suggested that Jews were a culturally “alien” presence in England that should be segregated as part of the reconstruction of a unified Christian society. The Catholic Times was even more sympathetic to fascism and antisemitism. In 1933, the paper asked whether one can be “quite certain that the alleged Nazi persecution of the Jews is quite what it is made out to be?” According to the editorial, “we cannot easily forget the part played by international Jewry in the present state of world-distress. Nor can we overlook the fact that Jews are at the back of much of the present widespread propaganda of irreligion and immodesty, two of atheistic Communism’s main lines of attack on that civilisation which Herr Hitler, for all his faults, has sworn to uphold.” According to the editorial, “Jewish Freemasonry is at the back of a world-wide persecution of Catholics far worse than anything that Jews have had to suffer in Germany.” The Catholic Times even suggested that it was the “international Jews” that were “persecuting the Nazis.” According to an editorial in 1938, “if Fascism is tolerated by us, … it is not because it is opposed to Bolshevism, but because in many respects it is a good form of government. The evil in it can be tolerated because it is far outweighed by the good. Bolshevism, on the other hand, cannot be tolerated, because it is fundamentally and essentially evil, because the evil far outweighs the good.” (See for example, “Fascism,” Catholic Herald, 17 August 1935, p.10; “The Future of Jewry,” Catholic Herald, 3 January 1936, p.8; “Mosely Goes Anti-Semite,” Catholic Herald, 27 March 1936, p.6; “And the East End,” Catholic Herald, 23 October 1936, p.8; “The Resistance to Jewry,” Catholic Herald, 22 January 1937, p.8; “Herr Hitler and the Jews,” Catholic Times, 31 March 1933, p.10; “Mr. Vernon Bartlett’s Broadcast,” Catholic Times, 27 October 1933, p.10; “Why Fascism is Tolerable,” Catholic Times, 14 January 1938, p.10).

Unlike the Catholic Herald and the Catholic Times, the Catholic Worker was consistently critical of all forms of fascism, rejected the concept of a “Jewish Problem,” and refuted antisemitic accusations and stereotypes. According to the Catholic Worker soon after its founding in 1935, “the troubles of Germany in the last three years have steadily grown worse, and the persecution of both the Jews and the Catholic population has increased in its severity. … the governors of Germany would seem to have become hopelessly drunk of the wildest dreams of nationality, and the exaltation of a mad racial obsession.” The paper had no confidence that “the Hitler gangsters” would honour the Concordat between Germany and the Vatican. (“Germany and the Vatican: A Reply to Nazis,” Catholic Worker, August 1935, p.1).