Home » Posts tagged 'Chesterton'

Tag Archives: Chesterton

Cecil Chesterton and the Jews

Cecil Chesterton (1879-1918), like his close friend and fellow journalist-author Hilaire Belloc, and his brother G. K. Chesterton, frequently caricatured and stereotyped Jews in his newspaper articles (in particular in the Eye Witness and New Witness newspapers). A number of studies of Jewish stereotypes have shown that over the centuries, “the Jews” have occupied a special place in the Christian imagination. Sometimes they are stereotyped and deprecated as diabolic villains, and sometimes they are stereotyped and praised as virtuous, but they are rarely portrayed simply as normal human beings, with the same failings, virtues and gifts as everyone else. There are “good Jews” and there are “bad Jews”, but in either case, the Jew is different, distinct, “the other”. This observation would seem to apply in particular to Cecil Chesterton. On the one hand Cecil denied that he was antisemitic, rejected any call for Jews to be persecuted, and stated that he liked “many” Jews as individuals. For Cecil, there was something peculiar, quaint and foreign about Jews. He could not help but obsess with them. He stated that “even the less pleasant of them interest me merely because they are Jews” [my emphasis]. He explained that this interest arose because “their peculiarities fascinate me; the curious and often unexpected differences in the attitude of the mind, which mark them off from us, arrest my intelligence and pique my curiosity.” According to Cecil, “Jewish virtues,” “manners” and “morals” are distinct from those of Englishmen, and if that could only be admitted, those virtues could be admired in the same way that “the quaint virtues of the Chinese commend our admiration.” He stated that: “One would readily say to a friend: ‘do come to dinner on Tuesday: I have a Chinese gentleman coming, and he ought to be extraordinarily interesting.’ When people can say that about a Hebrew gentleman, anti-Semitism will be at an end.” Cecil Chesterton, The British Review, May 1913, 161-169.

As others have noted, Cecil was one of the principal anti-Jewish agitators during the prominent Marconi Affair. As far as Cecil was concerned, even though only two Jewish individuals (the Isaacs brothers) were implicated in the scandal, and were not alone in being accused, it was nevertheless a quintessentially Jewish affair. During this episode, in a satirical legal defence in the Eye Witness newspaper, Cecil Chesterton (writing under his nom de plume of Junius) patronisingly “defended” Rufus Isaacs specifically as a Jew, arguing that as a Jew, Rufus Isaacs could not be judged by, or be expected to understand, the morality of a Christian civilisation. He claimed that Rufus hid his Jewishness because he shared the “shyness” and secrecy which was “hereditary” in his “race,” but that it was this very Jewishness that constituted the core of his defence. According to Cecil, Rufus Isaacs should not be tried in an English court by an English jury as he is “not an Englishman” but a Jew. “He is an alien,” Cecil surmised, “a nomad, an Asiatic, the heir of a religious and racial tradition wholly alien from ours. He is amongst us: he is not of us.” He could not, Cecil deduced, be fairly “expected to understand the subtle workings of that queer thing the Christian conscience”. Cecil continued to attack Rufus Isaacs and his brother Godfrey Isaacs in a series of antisemitic articles in the New Witness (the successor to the Eye Witness). According to Cecil, one can locate the roots of the prosperity and political power of the Isaacs, along with other Jewish families, such as the Samuels and Rothschilds, in “usury,” “gambling with the necessities of the people,” and the “systematic bribery of politicians.” In addition to the stereotype of the greedy Jew, he also invoked the image of Jewish secrecy. According to Cecil Chesterton, when “a Jew commits the contemptible act of changing his name into some ludicrous pseudo-European one,” it was his duty to “draw attention to the plain truth about it.” Cecil Chesterton [Junius], “For the Defence: III. In Defence of Sir Rufus Isaacs,” Eye Witness, 4 July 1912, 77-78; Cecil Chesterton [Junius], “An Open Letter to Mr. Israel Zangwill,” New Witness, 19 December 1912, 201.

Cecil Chesterton’s hostility towards Jews was not however confined to, or instigated by, the Marconi scandal. As early as 1905, in a little known book entitled Gladstonian Ghosts, Cecil Chesterton informed his readers that towards the end of the nineteenth century, the “unclean hands of Hebrew finance” had pulled “the wires” of the progressive “Tory revival”. Cecil went on to warn that “one of these days our Hebrew masters will say to us: ‘Very well. You object to conditions; you shall have none. We will import Chinamen freely and without restriction, and they shall supplant white men, not in the mines only, but in every industry throughout South Africa.’” Cecil Chesterton, Gladstonian Ghosts (London: S. C. Brown Langham, [1905]), 17-18, 107.

The image of the Jews as “smart” and “intelligent” has always been something of a double-edged stereotype. On the one hand intelligence is admired, but on the other hand it can be coupled with arrogance and shrewd cunning. Cecil Chesterton’s friend, Hilaire Belloc, provides a clear illustration of this ambivalent stereotype. According to Belloc, one of the marks of “the Jew” is the “lucidity of his thought.” At his best, the Jew may be a devoted scientist or great philosopher. According to Belloc, he is “never muddled” in argument. However, he then goes on to explain that there is “something of the bully” in the Jew’s “exactly constructed process of reasoning.” A man arguing with a Jew, Belloc contended, may know the Jew to be wrong, but he feels the Jew’s “iron logic offered to him like a pistol presented at the head of his better judgement.” Hilaire Belloc, The Jews (London: Constable, 1922), 81. In 1908, in an anonymously published book entitled G. K. Chesterton: A Criticism, Cecil Chesterton combined the stereotype of the dangerously smart Jew with that of Jewish greed and usury. According to Cecil, Jews had brains, but they lacked all the honourable and chivalrous qualities of a gentleman. He asserted that “our aristocrats were proud of being strong, of being brave, of being handsome, of being chivalrous, of being honourable, of being happy, but never of being clever. The idea that brains were any part of the make-up of a gentleman was never dreamed of in Europe until our rulers fell into the hands of Hebrew moneylenders, who, having brains and not being gentlemen, read into the European idea of aristocracy an intellectualism quite alien to its traditions.” [Cecil Chesterton], G. K. Chesterton: A Criticism (London: Alston Rivers, 1908), 4-5.

Cecil also drew upon the myth of Jewish ritual murder – i.e. the blood libel – as part of his wider construction of Jewish villainy and foreignness. In March 1911, a thirteen year old Christian boy, Andrei Yushchinsky, went missing. His body was found a week later in a cave just outside Kiev. Approximately four months later, Mendel Beilis, a Ukrainian Jew, was accused of the murder. Initially the indictment was simply for murder, but subsequently the prosecution added the charge of ritual murder. This was based on a testimony by a lamplighter, who claimed that he had seen a Jew kidnap the child (the lamplighter apparently later confessed that he had been led into this testimony by the secret police). Beilis was accused of stabbing the child thirteen times, which was supposedly in accordance with a so-called Jewish rite; there was of course no such rite, and it was later revealed that there were over forty stab wounds. Beilis was incarcerated, tortured and interrogated, before finally being brought to trial and found innocent, after a two year wait, in September-October 1913. During this episode, antisemitic leaflets were circulated in Russia, suggesting that the Jews use the blood of Christian children to make Passover matzot, though a great many Russians also leapt to the defence of Beilis. On the international stage, so-called “experts” on the Jews and “ritual murder”, such as Father Pranaitis and authors for the Rome based journal, La Civiltà Cattolica, informed the world in gruesome detail about how Jews supposedly went about ritually murdering Christian children in order to obtain their blood for religious or magical rituals. La Civiltà Cattolica, a periodical constitutionally connected to the Vatican, published two articles which set out to present “medical opinion” to the effect that “death was brought about in three stages: the boy was stabbed in such a manner that all his blood could be collected, he was tortured, and finally his heart was pierced.” This alleged evidence was held by Civiltà Cattolica to indicate “ritual murder, which only Jews could perpetrate, since it required long experience.” “Jewish Trickery and Papal Documents – Apropos of a Recent Trial,” Civiltà Cattolica, April 1914, cited by Charlotte Klein, “Damascus to Kiev: Civiltà Cattolica on Ritual Murder,” in Alan Dundes, ed., The Blood Libel Legend (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991), 194-196.

In response to this episode, “the Beilis Affair,” Cecil Chesterton characterised Russian pogroms as something horrible, but also something to be understood as part of an ongoing “bitter historic quarrel” between Israel Zangwill’s people (i.e. “the Jews”) and the people of Russia. The “evidence of the pogroms”, he argued, points to a “savage religious and racial quarrel.” He suggested that it was sometimes “a naturally kindly people like the Russians [who] are led to perpetrate the atrocities,” and sometimes it was the “equally embittered” Jews, who, “when they got a chance of retaliating, would be equally savage.” Referring to the Beilis Affair, Cecil endorsed the blood libel, stating that: “An impartial observer, unconnected with either nation, may reasonably inquire why, if we are asked to believe Russians do abominable things to Jewish children, we should at the same time be asked to regard it as incredible … that Jews do abominable things to Russian children – at Kieff, for instance.” Israel Zangwill, a prominent Anglo-Jewish author and playwright, countered Cecil Chesterton’s accusation, noting that following his logic, we should have to accept that if hooligans throttle Quakers then Quakers must also be throttling hooligans. Zangwill also rightly pointed out that it was implausible that a Jew would murder a Christian child for ritual purposes considering no such ritual exists in Judaism. In response, Cecil Chesterton stated that “as to ‘ritual murder’, Mr. Zangwill, of course, knows that no sane man has ever suggested that it [ritual murder] was a ‘rite’ of the Jewish Church any more than pogroms are rites of the Greek Orthodox Church.” He then proceeded to clarify that what he and others had suggested, is that “there may be ferocious secret societies among the Russian Jews,” and that “as so often happens with persecuted sects, such societies may sanctify very horrible revenges with a religious ritual.” In other words, Cecil Chesterton accepted that responsible Jews did not go around committing ritual murder, but did suggest that a sect of fanatical and vengeful Jews did go around murdering Christian children following a “religious ritual”. Eleven years later, his brother, G. K. Chesterton, similarly suggested as part of his complex multifaceted construction of “the Jew,” that “ritual murder” had occasionally been committed by Jews, not by responsible practitioners of Judaism as such, but by “individual and irresponsible diabolists who did happen to be Jews”. Cecil Chesterton, “Israel and ‘The Melting Pot,’” New Witness, 5 March 1914, 566-567; Cecil Chesterton, “A Letter from Mr. Zangwill,” New Witness, 12 March 1914, 593-594; G. K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (London: Hodder and Stoughton, [1925]), 136.

Cecil Chesterton also revived the host desecration myth. He stated that “the Jews may or may not have insulted the Host, as was alleged. I do not know.” “But,” he continued, “I do know that they wanted to; because I know what a religion means, and therefore what a religious quarrel means.” This insight into what Cecil Chesterton considered expected conduct in a “religious quarrel” – and his belief that Jews would be involved in the destruction of host wafers, which hold no significance in Judaism – is revealing of his polemical and pugnacious anti-Jewish mindset. Cecil Chesterton, “Israel and ‘The Melting Pot,’” New Witness, 5 March 1914, 566.

Zionism and “Privilege” according to G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc

G. K. Chesterton, like his friend Hilaire Belloc, believed that the so-called “Jewish problem” was an intrinsic fact. In What I Saw in America (1922), he observed that if Henry Ford, the American automobile industrialist and antisemitic author of The International Jew, had “discovered that there is a Jewish problem, it is because there is a Jewish problem.” Americans, he observed, have inherited “a prejudice against Anti-Semitism; a prejudice of Anti-Anti-Semitism,” and yet even they “found the Jewish problem exactly as they might have struck oil; because it is there, and not even because they were looking for it.” G. K. Chesterton, What I Saw in America (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1922), 140-142.

Chesterton’s belief in the “Jewish problem” was manifest in a number of antisemitic stereotypes in his literature and journalism before and long after the Marconi Affair. The earliest example was the cowardly and secretive Jewish shopkeeper in “The Ball and the Cross,” which was first published as a feuilleton in the Commonwealth in 1905 and 1906, and later re-published as a book in 1910. G. K. Chesterton, “The Ball and the Cross,” Commonwealth: vol. 10, no. 3-12 (1905), and vol. 11, no. 1, 2, 4, 6, 11 (1906); G. K. Chesterton, The Ball and the Cross (London: Wells Gardner, Darton, 1910). The latest examples were a series of articles published in G.K.’s Weekly in the 1920s and 1930s. According to Chesterton, the greedy Jew, the Jewish Bolshevik, the Jewish coward, the unpatriotic Jew and the secretive Jew, were an intolerable irritant in Christian society. Chesterton also believed that Captain Dreyfus had probably been a German spy, arguing that the English press covered up all the evidence against him. He suggested that the heart of the matter was that the Jews living in England only masqueraded as Englishmen, rather than, as he conceived it, living openly as Jews. Chesterton fervently believed that to “recognize the reality of the Jewish problem is very vital for everybody and especially vital for Jews. To pretend that there is no problem is to precipitate the expression of a rational impatience, which unfortunately can only express itself in the rather irrational form of Anti-Semitism.” G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, 1920), 230-231.

Chesterton maintained his belief in the “Jewish problem” until the end of his life. In his Autobiography (1936), he stated that “I am not at all ashamed of having asked Aryans to have more patience with Jews or for having asked Anglo-Saxons to have more patience with Jew-baiters. The whole problem of the two entangled cultures and traditions is much too deep and difficult, on both sides, to be decided impatiently. But I have very little patience with those who will not solve the problem, on the ground that there is no problem to solve.” G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1936), 76.

It is often argued by his supporters that Chesterton could not have been antisemitic because he was a fervent supporter of Zionism. It is certainly true that motivated by his desire to solve the “Jewish Problem” by removing as many Jews from Europe as possible, Chesterton initially supported Zionism. Chesterton stated in The New Jerusalem (1920) that: “For if the advantage of the ideal to the Jews is to gain the promised land, the advantage to the Gentiles is to get rid of the Jewish problem, and I do not see why we should obtain all their advantage and none of our own. Therefore I would leave as few Jews as possible in other established nations.” G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, 1920), 248.

Jews leaving Europe was, Chesterton believed, simply the best way to remove the so-called “Jewish Problem”. Of course, as Owen Dudley Edwards rightly concluded in his essay in the Chesterton Review, “to say that a man wishes you and all your people to live somewhere else, is not to say that he likes you.” Owen Dudley Edwards, “Chesterton and Tribalism,” Chesterton Review VI, no.1 (1979-1980), 37.

In any case, Chesterton’s sympathy for Zionism did not last long. By 1925, the tone of his editorials in G.K.’s Weekly was ambivalent to Zionism. Zionism, one of his editorials argued, was falling into “the mud of mere commercialism.” The editorial suggested that there was “some good in the idea of Zionism; but Zionism does not include that good.” The purpose of Zionism, it observed, was to “relieve the pressure of the Jewish problem on all the other nations; to drain the Jewish element that lies everywhere in lakes or puddles, or wanders everywhere in streams or sewers, into that central sea of a real spiritual unity; the kingdom of Israel.” The problem, it contended, was that Zionism added a Jewish Problem in Palestine without diminishing it anywhere else. “We have,” it observed, “given him yet another country in which he can be an interloper and a nuisance.” The editorial concluded that the Jew is in Jerusalem as he is in any other part of the world, “but he is not at home there, for he cannot rest.” Another editorial in the paper stated that “the blow that destroyed our own Zionism was the Rutenberg Concession.” Chesterton observed that whilst he still believed in the concept of Zionism, he was now against the implementation of Zionism. He stated that he still believed in the idea of Zionism as a solution to the Jewish Problem, and that he would like to see it tried again. However, he now believed that Zionism should be attempted in some other place or places, such as Africa. Notes of the Week, G.K.’s Weekly, 4 April 1925, 27; G.K.’s Weekly, 2 May 1925, 126; Editor’s reply, The Cockpit, G.K.’s Weekly, 18 July 1925, 399-400.

For Belloc, the encounter between Jews and Christians was both a theological and socio-political conflict between fundamentally opposing factors. This can be seen in The Jews (1922). “The continued presence of the Jewish nation intermixed with other nations alien to it presents a permanent problem of the gravest character,” Belloc stated, and furthermore, he continued, “the wholly different culture, tradition, race and religion of Europe makes Europe a permanent antagonist to Israel.” Belloc drew his “solution” (i.e. a return to segregation) from the history of the Church. He explained that “wherever the Catholic Church is powerful, and in proportion as it is powerful, the traditional principles of the civilization of which it is the soul and guardian will always be upheld. One of these principles is the sharp distinction between the Jew and ourselves.” He stated that the “Catholic Church is the conservator of an age-long European tradition, and that tradition will never compromise with the fiction that a Jew can be other than a Jew. Wherever the Catholic Church has power, and in proportion to its power, the Jewish problem will be recognized to the full.” Belloc suggested that “recognition” was the solution successfully adopted by the Church for hundreds of years. He stated that segregation can be imposed by force or achieved by a mutual and amicable agreement in a way that satisfies both the “alien irritant” and the “organism segregating it.” Belloc hoped that the latter option could be adopted, with the Jews openly recognizing their “wholly separate nationality,” and the non-Jews, recognizing “that separate nationality, treating it without reserve as an alien thing, and respecting it as a province of society outside our own.” He argued that the term “segregation,” which he acknowledged “has a bad connotation,” may then be “replaced by the word recognition.” This he suggested was the most practical and moral solution. Hilaire Belloc, The Jews (London: Constable, 1922), 3-5, 209-210.

Belloc’s initial description of “recognition” implied that segregation would be “voluntary”. It was however a very odd sense of voluntariness. It was voluntary only if the Jews would embrace it; if they did not embrace it, it would be imposed anyway. At the end of his book he argued that if the proposal of recognition is “made on our side, the Jew may refuse any such bargain.” Belloc concluded that if he decides to “dig his heels in,” and continues to insist on full recognition as a Jew and as a member of “our” community, then “the community will be compelled to legislate in spite of him.” Recognition of separate national status would not be an abstract principle. He argued that Jewish institutions already in existence should be extended, such as Jewish schools, Jewish tribunals and the Jewish press, so that Jewish interaction with non-Jews can be minimised. He stated that once an atmosphere is created “wherein the Jews are spoken of openly, and they in their turn admit, define, and accept the consequences of a separate nationality in our midst,” then, finally, “laws and regulations consonant to it will naturally follow.” Belloc’s “solution” was to gradually return the Jews to a Jewish enclave or ghetto. Jews would be legally confined to operating within their own social and legal institutions and excluded from Christian civilisation. Hilaire Belloc, The Jews (London: Constable, 1922), 14, 271-274, 304.

Whilst Belloc employed the term “recognition” for his solution in The Jews in 1922, he had already outlined the core aspects of this solution in the Eye Witness in 1911, and referred to it as “privilege.” This was the exact same euphemism that Chesterton employed in the New Jerusalem in 1920. Whilst Chesterton initially supported Zionism and Belloc opposed it, there were significant similarities between their views. Chesterton stated that ideally “as few Jews as possible” would be left in other nations once they had the option of going to “the promised land,” and those who remain should, he suggested, be given “a special position best described as privilege; some sort of self-governing enclave with special laws.” “Of course,” he observed, “the privileged exile would also lose the rights of a native.” He stated that the Jews who remain in England should be allowed to occupy any occupation but with one important stipulation: they should be required to go about “dressed like an Arab.” He stated that “if my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.” This so-called “privileged position,” he believed, should not only be assigned to those Jews who choose to remain in England when they can go to the New Jerusalem; if Zionism fails, he stated, “I would give the same privileged position to all Jews everywhere, as an alternative policy to Zionism.” Hilaire Belloc, “The Jewish Question: VIII. The End – Privilege,” Eye Witness, 26 October 1911, 588-589; G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, 1920), 227, 248.

The antisemitic proposition that Jews should be required to wear distinctive clothing was not a new idea to Chesterton. As early as July 1913, seven years prior to The New Jerusalem, he had already reported that in the Middle Ages, it was “felt about the Jews, whether they were nice or nasty, whether they were impotent or omnipotent, was that they were different.” Chesterton stated that this recognition was expressed by “a physical artistic act, giving them a definite dwelling place and a definite dress.” This was a clear allusion to the ghetto and Judenhut. Chesterton however had different ideas about appropriate though equally distinctive clothing. The Jews should not, he argued, be “excluded from any civic rights when they obey the civic order,” but conversely they should, Chesterton concluded, be required to “wear Arab costume.” He stated that: “By all means let [a Jew] be Lord Chief Justice; but let him not sit in wig and gown, but in turban and flowing robes.” Chesterton concluded that “if the Jew were dressed differently we should know what he meant; and when we were all quite separate we should begin to understand each other.” G. K. Chesterton, “What shall we do with our Jews?”, New Witness, 24 July 1913, 370.

Whilst Chesterton’s suggestion that all Jews should be legally required to wear distinctive “Arab costume” when in public was a part of his peculiarly Chestertonian construction of the Jew (exhibiting his prejudice against both Arabs and Jews), he closely followed Belloc in suggesting so-called “privilege” (i.e. segregation) as the alternative solution for those Jews who remained in England. Whilst they disagreed about Zionism, their solutions and terminology for the so-called “Jewish Problem”, at least for those Jews who remained in England, were very similar. This was summed up in the New Witness (the magazine that G. K. Chesterton owned and edited), according to which the “ideal solution” for getting rid of the Jews was Zionism, whereas the “alternative solution” was so-called “privilege (their euphemism for segregation). “The Case for Oscar Levy,” New Witness, 7 October 1921, 194.

For more on G. K. Chesterton’s antisemitic stereotypes of “the Jew” and his constructions of the so-called “Jewish problem” and its so-called “solution”, please see Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G. K. Chesterton (2013).

G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of the Jewish Coward

The stereotype of the cowardly Jew, though less prominent than the greedy Jew and the Jewish Bolshevik stereotypes in his discourse, was another feature in Chesterton’s antisemitic construction of “the Jew.” He argued that bravery and patriotism were foreign to the Jewish makeup. This antisemitic stereotype appeared in particular in 1917 and 1918. For Chesterton, the virtues of bravery, chivalry and patriotism were intertwined. That the Jews did not share these “Christian” qualities was, Chesterton believed, a point that should be understood, even excused, but certainly recognised. In an article on 11 October 1917, he stated that he felt “disposed to gibbet the journalist at least as much as the Jew; for the same journalism that has concealed the Jewish name has copied the Jewish hysteria.” According to Chesterton, “at least the wretched ‘alien’ can claim that if he is scared he is also puzzled; that if he is physically frightened he is really morally mystified. Moving in a crowd of his own kindred from country to country, and even from continent to continent, all equally remote and unreal to his own mind, he may well feel the events of European war as meaningless energies of evil. He must find it as unintelligible as we find Chinese tortures.” Chesterton claimed that he was inclined to “the side of mercy in judging the Jews,” at least in comparison to certain newspaper “millionaires.” He argued that a Jew with a gold watch-chain “grovelling on the floor of the tube” was not as ugly a spectacle as the newspaper millionaires who multiply their “individual timidity in the souls of men as if in millions of mirrors.” Chesterton was willing to accept that there were rare and exceptional Jews who won medals for bravery, but he was not willing to concede this to more than a small number of Jews. Such Jews, he argued, were rare, and so they should be honoured not merely as “exceptionally heroic among the Jews,” but also as “exceptionally heroic even among the heroes.” Chesterton concluded that it “must have been by sheer individual imagination and virtue that they pierced through the pacifist materialism of their tradition, and perceived both the mystery and the meaning of chivalry.” G. K. Chesterton, “The Jew and the Journalist,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 11 October 1917, pp. 562-563.

When later quizzed by Leopold Greenberg, the proprietor-editor of the Jewish Chronicle and the Jewish World, on 14 June 1918, as to whether he himself had witnessed Jews cowering in tube stations, Chesterton admitted that he had not personally witnessed this, but he argued that it was a matter of common knowledge. In an article on 21 June 1918, he stated that “the problem of aliens in air-raids is a thing that everybody knows.” He suggested that he could hardly be expected to go looking “for Jews in the Tubes, instead of going about my business above ground.” Chesterton concluded that if his affairs had led him into the Tubes during an air raid, he would probably have seen what others have reported, and the editor of the Jewish Chronicle and the Jewish World would no doubt have “refused my testimony as he refused theirs.” Somewhat patronizingly, Chesterton “excused” the Jew of his so-called cowardice during air raids, attributing it to the “psychological effect of a Gotha on a Ghetto”. He explained that he himself had “defended the Jew so situated; comparing him for instance to a Red Indian who might possibly be afraid of fireworks, to which he was not accustomed, and yet not afraid of slow fires, to which he was accustomed.” G. K. Chesterton, At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 21 June 1918, pp. 148-149. See also “A Reckless Charge,” Jewish Chronicle, 14 June 1918, 4.

Whilst Chesterton claimed that he was inclined towards mercy in judging cowardice, he was utterly unprepared to tolerate “pacifism”. Articles in 1917 and 1918 suggested that pacifism elevated cowardice to an ideal and denigrated bravery as a vice. It is one thing, he argued, to “feel panic and call it panic,” quite another to “cultivate panic and call it patriotism.” Chesterton regarded “absolute pacifism and the denial of national service simply as morally bad, precisely as wife-beating or slave-owning are morally bad.” He directed some “words of advice” to the Jews. He stated that “in so far as you say that you yourself ought not to be made to serve in European armies, I for one have always thought you had a case; and it may yet be possible to do something for you, … If you say that you ought not to fight, at least we shall understand. If you say that nobody ought to fight, you will make everybody in the world want to fight for the pleasure of fighting you.” Referring to Jews, he stated that “if they talk any more of their tomfool pacifism to raise a storm against the soldiers and their wives and widows, they will find out what is meant by Anti-Semitism for the first time.” G. K. Chesterton, “The Jew and the Journalist,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 11 October 1917, pp. 562-563 and G. K. Chesterton, “The Grand Turk of Tooting,” Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 25 October 1917, pp.610-611.

The reality is that during the First and Second World Wars, Anglo-Jews signed up for the armed forces with great enthusiasm. Despite this, Chesterton was not alone in embracing this antisemitic stereotype. As Tony Kushner (1989), Professor of the History of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton (and director of the Parkes Institute), has rightly stated: “On pure statistical grounds there was again no basis for the Jewish war shirker image to come about. To explain its pervasive appeal one has, as usual, to examine the past Jewish stereotype. The most significant aspect in this respect was the combined image of the cowardly and non-physical Jew.” Kushner explains that “the combined image of Jews as weak, cowardly, alien and powerful were all strongly ingrained in the public mind. Indeed the strength of such imagery is highlighted by the experience of Jews in the British Forces during the Second World War. As was the case in the 1914-18 conflict, a disproportionate number of Jews joined the Forces – 15% of Anglo-Jewry or 60,000 men and women compared to 10% of the population as a whole.” Tony Kushner, The Persistence of Prejudice: Antisemitism in British society during the Second World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), 122-123.

For more on this and other stereotypes and caricatures in Chesterton’s discourse, please see my recent book, Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G. K. Chesterton.

G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Greedy Jew”

Prior to the twentieth century, G. K. Chesterton expressed sympathy for Jews and hostility towards antisemitism. He was agitated by Russian pogroms and felt sympathy for Captain Dreyfus. However, early into the twentieth century, he started to fear the presence of Jews in Christian society. He started to argue that it was the Jews who oppressed the Russians rather than the Russians who oppressed the Jews, and he suggested that Dreyfus was not as innocent as the English newspapers claimed (click link for more on Chesterton and Dreyfus). His caricatures of Jews were often that of grotesque creatures dressed up as English people. His fictional and his non-fictional works repeated antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish greed, usury, capitalism, bolshevism, cowardice, disloyalty and secrecy (each of these stereotypes are examined in detail in my recent book, Chesterton’s Jews). In this blog post, I will briefly examine Chesterton’s stereotype of the greedy usurious Jew.

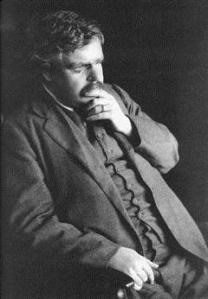

G. K. Chesterton

It has been argued by a number of Chesterton’s defenders that if Chesterton did harbour ill will towards Jews, then it was only to particular Jews (such as Rufus and Godfrey Isaacs), that it was only subsequent to the notorious Marconi affair, and that it faded after a few years. Chesterton’s stereotyping of the greedy usurious Jew did not in fact revolve around the Marconi Affair and was not confined to particular individuals. His antisemitic stereotype of the greedy Jew can be partly traced to his idealisation of the Middle Ages and his critique of modernity. Chesterton traced many of the problems of modernity back to the Reformation, which he suggested tore Europe apart faster than the Catholic Church could hold it together [1]. He was romantically attracted to the Middle Ages, which he imagined to be a relatively well-ordered period in history, with happy peasants, Christianity as a healthy part of every-day life, and the trades managed equitably and protected by the Church and the guild system. The medieval guilds, he suggested, prevented usury from disrupting the balance of society and destroying the livelihood of the peasantry.

The usurers and plutocrats that Chesterton had in mind were Jewish. In his A Short History of England, published in 1917, Chesterton implied that the Jews were not as badly treated in the Middle Ages as often portrayed, though they were sometimes handed over to “the fury of the poor,” whom they had supposedly ruined with their usury [2]. In order to obtain the vast sums demanded by King John in the early thirteenth century, Jews were arrested, property seized, some Jews were hanged, and one Jew had several teeth removed to persuade him to pay the sums demanded. Even poor Jews had to pay a tax or leave the kingdom [3]. However, according to Chesterton, the idea that Jews were compelled to hand over money to King John or have their teeth pulled was a fabrication: “a story against King John” rather than about him. He suggested that the story was “probably doubtful” and the measure, if it was enacted, was “exceptional.” The Christian and the Jew, he claimed, had “at least equal reason” to view each other as the ruthless oppressor. “The Jews in the Middle Ages,” he asserted, were “powerful,” “unpopular,” “the capitalists of the age” and “the men with wealth banked ready for use” [4].

Chesterton repeated a similar narrative about King John (and Richard Lion-Heart) in his newspaper, the G.K.’s Weekly: “John Lackland, as much as Richard Lion-Heart, would have felt that to be in an inferior and dependent position towards Isaac of York for ever was utterly intolerable. A Christian king can borrow of the Jews; but not settle down to an everlasting compromise, by which the Jews are content to live on his interest and he is content to live on their clemency” [5].

According to Chesterton, “medieval heresy-hunts spared Jews more and not less than Christians” [6]. A reoccurring hero in many of Chesterton’s short stories was Father Brown. Dale Ahlquist (2003), one of Chesterton’s staunch defenders, observes that Father Brown and Chesterton share the same “moral reasoning” [7]. This would seem to be confirmed in “The Curse of the Golden Cross” (1926). In this story, Father Brown, like Chesterton, argued that it was a myth that Jews were persecuted in the Middle Ages: “‘It would be nearer the truth,’ said Father Brown, ‘to say they were the only people who weren’t persecuted in the Middle Ages. If you want to satirize medievalism, you could make a good case by saying that some poor Christian might be burned alive for making a mistake about the Homoousion, while a rich Jew might walk down the street openly sneering at Christ and the Mother of God’” [8].

In The New Jerusalem (1920), Chesterton again argued that Jews were inclined to usurious practices. It was not just the Jews that he caricatured. He also repeated stereotypes about “gypsy” (or sometimes “gipsey” in Chesterton’s parlance [9]) pilfering and kidnapping (link for more on Chesterton and the stereotype of the child-kidnapping “gypsy”). He suggested that a comparison may be made between “Gipsey pilfering” and “Jewish usury.” Both “races,” he observed, “are in different ways landless, and therefore in different ways lawless.” Chesterton referred to the pilfering of chickens by “gypsies”, and the kidnapping of children, which he correlated to Jewish usury and fencing. He outlined his case as follows: “It is unreasonable for a Jew to complain that Shakespeare makes Shylock and not Antonio the ruthless money-lender; or that Dickens makes Fagin and not Sikes the receiver of stolen goods. It is as if a Gipsey were to complain when a novelist describes a child as stolen by the Gipseys, and not by the curate or the mothers’ meeting. It is to complain of facts and probabilities.” He concluded that “there may be good Gipseys” and “good qualities which specially belong to them as Gipseys.” “Students of the strange race,” he observed, have even “praised a certain dignity and self respect among the women of the Romany. But no student ever praised them for an exaggerated respect for private property, and the whole argument about Gipsey theft can be roughly repeated about Hebrew usury” [10].

The problem of the wandering Jewish financier, Chesterton suggested, was not confined to Europe. He argued in G.K.’s Weekly that America was the new pied a terre of the international Jewish financier, and that it was for the sake of such Jews that Britain has “clung to the American skirts” [11]. The stereotype of the greedy plutocratic Jew can also be found in Chesterton’s short stories and novels. For example, at the conclusion of “The Bottomless Well,” Horne Fisher, the detective protagonist of the story, engages in a diatribe against the Jews. “It’s bad enough,” he observed, “that a gang of infernal Jews should plant us here, where there’s no earthly English interest to serve, and all hell beating up against us, simply because Nosey Zimmern has lent money to half the Cabinet.” He went on to state: “But if you think I am going to let the Union Jack go down and down eternally like the Bottomless Well, down into the blackness of the Bottomless Pit, down in defeat and derision amid the jeers of the very Jews who have sucked us dry – no, I won’t, and that’s flat; not if the Chancellor were blackmailed by twenty millionaires with their gutter rags, not if the Prime Minister married twenty Yankee Jewesses” [12]. Another story, “The Five of Swords,” revolves around cowardly Jewish moneylenders who ruin and murder their victims [13].

One question that may be asked is what led Chesterton to embrace this and other antisemitic stereotypes. One possible answer is that his closest friend, Hilaire Belloc, convinced him of their veracity. Chesterton and Belloc met in 1900. By 1904, Chesterton was working with Belloc on his novel Emmanuel Burden (providing Belloc with a number of sketches for the characters in his novel, including the main antagonist, I. Z. Barnett, who is portrayed as a greedy, manipulative and fraudulent German Jew). In this novel, Barnett formulated a project, the “African M’Korio” scheme, which involved the manipulation of the stock market, the exploitation of Africa, and the destruction of Emmanuel Burden, a naïve but honest British merchant. It was not just in his fiction that Belloc constructed his image of exploitive Jews in Africa. In a letter to Chesterton in 1906, Belloc stated that he was “now out against all Vermin: notably South African Jews”. Significantly, it was around this time that Chesterton started to stereotype Jews in his own fiction – the earliest example being the cowardly and secretive Jewish shopkeeper in The Ball and the Cross, which was first published as a feuilleton in the Commonwealth in 1905/6. [14].

Hilaire Belloc

Another stereotype of “the Jew” that was prominent in Chesterton’s discourse (and shared by Belloc) was the Jewish Bolshevik. Chesterton often closely linked this stereotype to that of Jewish bankers, usurers and capitalists. He maintained that the rich Jewish capitalists and poor Jewish Bolsheviks were merely the other side of, if not closely associated and allied with, each other. He argued that “Big Business and Bolshevism are only rivals in the sense of making rival efforts to do the same thing; and they are more and more even doing it in the same way. I am not surprised that the cleverest men doing it in both cases are Jews.” According to Chesterton, the “whole point” of the New Witness was to maintain that “Capitalism and Collectivism are not contrary things. It is clearer every day that they are two forms of the same thing” [15]. The stereotype of the Jewish Bolshevik, which was almost as pervasive in Chesterton’s discourse as that of the greedy usurious Jew, will be examined in my next blog post on Chesterton (click here for link to G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Jewish Bolshevik”).

.

Notes for G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Greedy Jew”

1. G. K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong with the World (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1910), 42.

2. G. K. Chesterton, A Short History of England (London: Chatto & Windus, 1917), 108-109.

3. Anthony Julius, Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 118-119, 643 fn.82-84.

4. G. K. Chesterton, A Short History of England (London: Chatto & Windus, 1917), 108-109.

5. G. K. Chesterton, “The Neglect of Nobility,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 4 August 1928, 327.

6. G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1936), 76.

7. Dale Ahlquist, G. K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003), 166.

8. G. K. Chesterton, “The Curse of the Golden Cross,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Complete Father Brown Stories (London: Wordsworth Classics, 2006), 432. This short story was originally published in 1926.

9. The strange spelling of “gipsey” is Chesterton’s. The spelling has been changed in some later editions of The New Jerusalem.

10. G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, [1920]), 232. An editorial in G.K.’s Weekly repeated the same stereotypes linking the so-called child-kidnapping “gypsy” with the usurious Jew. See G.K.’s Weekly, 2 May 1925, 126.

11. G. K. Chesterton, “Exodus from Europe,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 28 December 1929, 247.

12. G. K. Chesterton, “The Bottomless Well,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Other Stories (London: Cassell, 1922), 73.

13. G. K. Chesterton, “The Five of Swords,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Other Stories (London: Cassell, 1922), 255-282.

14. See Hilaire Belloc, Emmanuel Burden (London: Methuen, 1904); Letter from Hilaire Belloc to G. K. Chesterton, February 1906, ADD MS 73190, fol. 14, G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library Manuscripts, London; G. K. Chesterton, “The Ball and the Cross,” Commonwealth: vol. 10, no. 3-12 (1905), and vol. 11, no. 1, 2, 4, 6, 11 (1906).

15. G. K. Chesterton, “Rothschild and the Roundabouts,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 17 November 1922, 309-310.

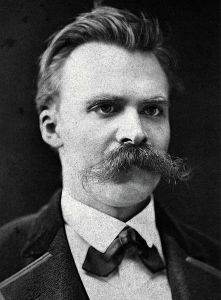

A look at G. K. Chesterton and Oscar Levy on the “169th birthday” of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

As Heather Saul in the Independent observes, today’s “Google Doodle” (15/10/2013) celebrates the “169th birthday” of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. As G. K. Chesterton’s “holiness” and “antisemitism” are currently being discussed and debated in various internet forums, it seems an opportune moment to look at some of his exchanges with Oscar Levy, a prominent German Jewish Nietzsche scholar in the early twentieth century.

Oscar Levy was probably the main advocate of Nietzsche’s ideas in Britain during the early decades of the twentieth century (he settled in Britain in the 1890s and he described himself as “a Nietzschean Jew”). Like Nietzsche, he was also deeply critical of Judaism and Christianity. According to Professor Dan Stone, Levy’s essential position was as follows: “modern European society is degenerating because it is bound to an effete moral value system; these effete values derive from Judaism”. Levy argued that “this Jewish ethic was taken a step further by Christianity, which is a ‘Super-Semitism’” [1]. Following Nietzsche, Levy argued that Christianity was a development of Judaism, and that both were manifestations of a slave mentality. According to Levy, “the Semitic idea has finally conquered and entirely subdued this only apparently irreligious universe of ours.” He stated that “it has conquered it through Christianity, which of course, as Disraeli pointed out long ago, is nothing but ‘Judaism for the people’” [2].

Clearly Levy and Chesterton could not have been more diametrically opposed to each other when it came to their views on Nietzsche (and Christianity). Chesterton dismissed Nietzsche on a number of occasions as a raving madman; Levy celebrated Nietzsche as a clear-sighted diagnostician. However, they shared one thing in common: they both viewed and portrayed Bolshevism with concern if not disdain. Their essays and articles were peppered with disparaging remarks about Bolshevism, and they both suggested that Bolshevism was a Jewish movement. Discussing “the Jewish element in Bolshevism,” Chesterton argued that “it is not necessary to have every man a Jew to make a thing a Jewish movement; it is at least clear that there are quite enough Jews to prevent it from being a Russian movement” [3]. He stated that “there has arisen on the ruins of Russia a Jewish servile State, the strongest Jewish power hitherto known in history. We do not say, we should certainly deny, that every Jew is its friend; but we do say that no Jew is in the national sense its enemy” [4].

When Levy argued that Bolshevism was a Jewish movement, Chesterton and Belloc at first believed they had found a Jew they could identify with and support. They either ignored or did not notice his criticisms of Christianity. When the British Home Office arranged for Levy to be expelled from Britain, they argued that the Jews had arranged it in revenge for his deprecating remarks about Judaism. Belloc wrote in The Jews in 1922 that “the case of Dr. Levy turned out of this country by his compatriots in the Government for having written unfavourably of the Moscow Jews will be fresh in every one’s memory” [5]. Referring to Dr Oscar Levy, Chesterton stated in 1926 that he had “a great regard for him, which is more than a good many of his countrymen or co-religionists can say.” According to Chesterton: “He is a very real example of a persecuted Jew; and he was persecuted, not merely by Gentiles, but rather specially by Jews. He was hounded out of this country in the most heartless and brutal fashion, because he had let the cat out of the bag; a very wild cat out of the very respectable bag of the commercial Jewish bagman. He told the truth about the Jewish basis of Bolshevism, though only to deplore and repudiate it” [6].

After supposedly defending Levy from the Jews, Chesterton must have felt a little disappointed with Levy’s reply. Oscar Levy wrote to Chesterton, pointing out that he was not driven out of England by Jews at all, that the astonishing thing was that his statements about Jews and Judaism had “created so little stir amongst them,” and that the Jewish Chronicle and Jewish World had supported him against the decision by the Home Office [7]. Levy argued that Bolshevism was more closely related to Christianity than to Judaism. In this he was of course constructing a caricature of Christianity and so-called Christian Bolshevism in much the same way that Chesterton caricatured Jewish culture and so-called Jewish Bolshevism. He denied that “these Russian Jews, who are Jews in race, are also Jews in spirit.” “They are not,” he concluded, “they are really Christians. The Jewish mind has a great affinity to Christianity: the first Christians were one and all Jews, and these latter-day Jews are likewise all imbued with the Christian Spirit (though they themselves are entirely unaware of this). But the Jew on the whole is not a Christian …” According to Levy, “the doctrine of the Bolshevists is then – au fond – a Jewish doctrine, in as much as Christianity is a Jewish creed.” [8].

The idea that the Anglo-Jewish community pulled the strings of the Home Office to arrange for Levy to be removed from Britain was simply a Bellocian and Chestertonian antisemitic invention. In fact it was not only the Jewish Chronicle and Jewish World (the two most prominent Anglo-Jewish newspapers at the time) that argued that Levy should be allowed to stay. The other prominent Anglo-Jewish newspaper, the Jewish Guardian, also defended his right to stay in Britain. The Jewish Guardian expressed relief that the Chief Rabbi added his name to the appeal to allow Oscar Levy to stay. The Jewish Guardian did not admire Oscar Levy’s views or his decision to write a preface for George Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers (an antisemitic conspiracy theorist), but it did not believe that it was right for an Act of Parliament to be administered against Levy on the basis of his philosophical theories [9].

Notes for A look at G. K. Chesterton and Oscar Levy on the “169th birthday” of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

1. Dan Stone, “Oscar Levy: A Nietzschean Vision,” in Breeding Superman: Nietzsche, Race and Eugenics in Edwardian and Interwar Britain (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002), pp.12-32.

2. Oscar Levy, “Prefatory Letter,” in George Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers, The World Significance of the Russian Revolution (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1920), vi.

3. G. K. Chesterton, “The Beard of the Bolshevist,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 14 January 1921, p.22.

4. G. K. Chesterton, “The Feud of the Foreigner,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 20 August 1920, p.309.

5. Hilaire Belloc, The Jews (London: Constable, 1922), p.193, footnote 1.

6. G. K. Chesterton, “The Napoleon of Nonsense City,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 14 August 1926, pp.388-389.

7. Letter from Oscar Levy to the editor of G.K.’s Weekly, “Dr. Oscar Levy and Christianity,” The Cockpit, 13 November 1926, p.126. For examples of these newspapers defending Oscar Levy’s right to stay in England, see “Dr. Oscar Levy,” Jewish Chronicle, 16 September 1921, p.10; “Dr. Oscar Levy,” Jewish Chronicle, 30 September 1921, p.10; “Dr. Oscar Levy,” Jewish Chronicle, 7 October 1921, p.7; “The Case of Dr. Oscar Levy,” Jewish World, 4 May 1922, p.5.

8. Letter from Oscar Levy to the editor of G.K.’s Weekly, “Mr. Nietzsche Wags a Leg,” The Cockpit, 2 October 1926, 44-45; Letter from Oscar Levy to the editor of G.K.’s Weekly, “Dr. Oscar Levy and Christianity,” The Cockpit, 13 November 1926, p.126.

9. See “The Case of Dr. Levy,” Jewish Guardian, 14 October 1921, pp. 1, 3.

“Ludicrous, surreal” defence of G. K. Chesterton

A few days ago, Michael Coren reported a so-called “ludicrous, surreal episode” [1]. The episode in question was a Twitter discussion about a claim made in one of his books that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism. From the language employed, one might imagine a particularly bitter exchange, for Coren uses phrases such as the following to describe – and presumably to deter – those who dare to criticise Chesterton: “monomania, wrapped in the last acceptable prejudice of anti-Catholicism,” “the fundamentalism of those so committed to damaging Chesterton’s reputation,” and “the most extreme, bizarre lengths to have their way” [1]. The ad hominem tactic of dismissing out of hand the critics of Chesterton as “anti-Catholic” is regrettable and unfounded (especially as the discussion in question focused on Chesterton and the Wiener Library and not Chesterton’s Catholicism). Speaking for myself, I harbour no hostility for Catholics or Catholicism, and my concerns about Chesterton end with his hostile stereotypes and caricatures (about Jews and other “Others”). If I harbour a prejudice it is – to use a phrase once used by Chesterton to describe the sentiments of Americans – “a prejudice against Anti-Semitism; a prejudice of Anti-Anti-Semitism” [2].

But back to the article. Coren points out that he devoted a chapter to the issue of Chesterton’s discourse about Jews, and that only “one brief passage concerned London’s Wiener Library, a small institution devoted to the study of the Holocaust and anti-Semitism.” He stated that: “I spent a morning there in 1985 and discussed my research with a librarian. He told me that Chesterton was never seriously anti-Semitic. ‘He was not an enemy, and when the real testing time came along he showed what side he was on.’” Coren then expresses his indignation that “a self-published writer in Britain” – a reference to my recent examination of Chesterton’s stereotyping in Chesterton’s Jews – “demanded a name, proof, a reference.” “Sorry, mate: no name, no proof, and it was, as I say, a quarter of a century ago,” Coren replies. [1]

If Coren had originally stated merely that he had discussed his research with “a librarian” and that this librarian had defended Chesterton, then this would indeed be a relative non-issue (though a source citation would still have been useful). However, in the New Statesman in 1986 he attributed the defence of Chesterton to “the Wiener Institute” [3]. And in his biography of Chesterton the statement in defence of Chesterton is attributed to “the Wiener Library” [4]. There is of course a world of difference between the personal sentiment of an unnamed librarian and the position of the Wiener Library. Interestingly, he now describes the Wiener Library as “a small institution,” whereas back in 1986 when he was citing the Wiener Library in defence of Chesterton, he described the Wiener Library as “the best monitors of anti-semitism in Britain” [3].

The real issue is not Coren’s book per se – as he acknowledges, there have been plenty of subsequent biographies of Chesterton, and “some of them, frankly, rather better” than his [1]. However, subsequent authors have taken Coren’s earlier claim that the Wiener Library defended Chesterton at face value, and have repeated it in books, articles and web sites. As Ben Barkow, the current director of the Wiener Library states, “numerous websites cite a made-up quotation by the Library stating that Chesterton was not antisemitic. Our efforts to have these false attributions removed have largely failed” [5]. As a result, the myth that the Wiener Library defends Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism has acquired currency, when according to Coren’s latest article, he only discussed his research with an unnamed librarian he once met there [1] [6].

Turning to Coren’s other main point, he observes that Chesterton was “an early anti-Nazi” [1]. Here Coren is on safer – which is not to say solid – ground, and many of Chesterton’s defenders make the same point. Chesterton was anti-Nazi and it would be unfair to equate his particular brand of anti-Jewish discourse with Nazi antisemitism. However, if we are going to be fair and balanced, we should also point out that often in the very same articles in which Chesterton criticised Nazi antisemitism, he also repeated the stereotypes and caricatures of Jews that he had maintained before the 1930s. His defence of Jews was therefore not without its equivocation. Let’s look at a few examples. In March 1933, he criticised Hitler’s antisemitism, but then repeated his old claim that the English were never allowed to hear that “Dreyfus had got leave to go to Italy and used it to go to Germany; or that he was seen in German uniform at the German manoeuvres” [7]. In July 1933, he criticised “Hitlerism”, but then observed that it was “only just to Hitler” to point out that the Jews “have been too powerful in Germany.” He stated that “it is but just to Hitlerism to say that the Jews did infect Germany with a good many things less harmless than the lyrics of Heine or the melodies of Mendelssohn. It is true that many Jews toiled at that obscure conspiracy against Christendom, which some of them can never abandon; and sometimes it was marked not be obscurity but obscenity. It is true that they were financiers, or in other words usurers; it is true that they fattened on the worst forms of Capitalism; and it is inevitable that, on losing these advantages of Capitalism, they naturally took refuge in its other form, which is Communism” [8]. In November 1934, he criticised “the Hitlerites”, but then stated that: “There is a Jewish problem; there is certainly a Jewish culture; and I am inclined to think that it really was too prevalent in Germany. For here we have the Hitlerites themselves, in plain words, saying they are a Chosen Race. Where could they have got that notion? Where could they even have got that phrase, except from the Jews?” [9]. (For more on Chesterton’s discourse about Hitler and the Jews, see G. K. Chesterton discussing Hitler and the Jews, 1933-1936).

Coren concludes that he would rather be in the “valley with Gilbert than the peak with his critics,” because according to Chesterton it is possible to see “only small things from the peak” [1]. If viewing Chesterton’s discourse from the valley means missing such “small” details as these, then I am happy to occupy “the peak with his critics.”

.

Notes for “Ludicrous, surreal” defence of G. K. Chesterton

1. Michael Coren, “‘Ludicrous, surreal episode’ against G. K. Chesterton returns,” The B.C. Catholic, 13 September 2013, http://bcc.rcav.org/opinion-and-editorial/3069-canonization-attempt-resurrects-anti-semitic-claim (downloaded 17 September 2013).

2. G. K. Chesterton, What I Saw in America (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1922), 140-142.

3. Michael Coren, “Just bad friends,” review of G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, by Michael Ffinch, New Statesman, 8 August 1986, 30.

4. Michael Coren, Gilbert: The Man Who Was G. K. Chesterton (London: Jonathan Cape, 1989), 209-210.

5. Ben Barkow, “Director’s Letter,” Wiener Library News, Winter 2010, 2.

6. For an examination of this resilient myth, see Simon Mayers, “The resilient myth that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism,” 1 September 2013, https://simonmayers.com/2013/09/01/the-resilient-myth-that-the-wiener-library-defends-g-k-chesterton-from-the-charge-of-antisemitism/ (downloaded 17 September 2013).

7. G. K. Chesterton, “The Horse and the Hedge,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 30 March 1933, 55.

8. G. K. Chesterton, “The Judaism of Hitler,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 20 July 1933, 311-312.

9. G. K. Chesterton, “A Queer Choice,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 29 November 1934, 207.

Israel Zangwill and G. K. Chesterton: Were they friends?

In a previous report I examined the resilient myth that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism. In this posting I raise a more complex question: what was the relationship that existed between the prominent Anglo-Jewish author, Israel Zangwill, and G. K. Chesterton?

Michael Coren stated in 1989 that Israel Zangwill was a friend of Chesterton, describing them as a “noted literary combination of the time.”[1] Joseph Pearce has likewise reported that Israel Zangwill was someone with whom Chesterton had “remained good friends from the early years of the century until Zangwill’s death in 1926.”[2] One of the pieces of evidence of a friendship, circumstantial at best, is a photograph of Chesterton and Zangwill walking side by side after leaving a parliamentary select committee about the censorship of stage plays on 24 September 1909. The photograph was originally used for the front cover of the Daily Mirror on 25 September 1909. As they were both prominent authors, it is hardly shocking that they would both attend and give evidence at such a gathering. The photograph probably demonstrates little beyond that they shared an interest in government censorship and that they left the meeting at the same time (there is simply no way to tell for sure). According to an entire issue of Gilbert Magazine (2008) that was dedicated to defending Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism, Zangwill and Chesterton “had respect and admiration for one another.”[3] The photograph of them leaving the select committee on censorship was used as the front cover of the issue of Gilbert Magazine.[4] It has also been used in a number of other books and periodicals about Chesterton.

Chesterton and Zangwill after a parliamentary select committee about the censorship of stage plays on 24 September 1909

Prior to 1915, Chesterton had on occasion referred to Zangwill in positive terms, describing him as a “great Jew,” “a very earnest thinker,” and the “nobler sort of Jew.”[5] Likewise, Zangwill wrote a letter in 1914 and another in January 1915 which together suggest that an amicable relationship may have existed for a time (possibly until 1916). In 1914, he wrote to apologise for not being able to attend a public debate with Chesterton and several other people about the veracity of miracles. The letter was friendly though somewhat equivocal in its expressed sympathy for Chesterton’s play.[6] On 25 November 1914, Chesterton was overcome by dizziness whilst presenting to students at Oxford. Later that day he collapsed at home. He was critically ill, and it was feared that he might not survive. Whilst he did not fully recover until Easter, his wife reported on 18 January 1915 that he was showing some signs of recovery.[7] On 19 January, Israel Zangwill wrote a letter to Frances Chesterton, in which he expressed his pleasure at hearing that her husband was on the mend.[8]

Whatever the nature of their relationship, it did not prevent Chesterton from accusing Zangwill in 1917 of being “Pro-German; or at any rate very insufficiently Pro-Ally.” He suggested that “Mr. Zangwill, then, is practically Pro-German, though he probably means at most to be Pro-Jew.”[9] Their so-called friendship also did not prevent Zangwill from describing Chesterton as an antisemite. In The War for the World (1916), Zangwill dismissed the New Witness as the magazine of a “band of Jew-baiters,” whose “anti-Semitism” is rooted in “rancour, ignorance, envy, and mediaeval prejudice.” He suggested that G. K. Chesterton provided the “intellectual side” of the movement, which was, he concluded, “not strong except in names.” He stated that “Mr. G. K. Chesterton has tried to give it some rational basis by the allegation that the Jew’s intellect is so disruptive and sceptical. The Jew is even capable, he says, of urging that in some other planet two and two may perhaps make five.” Zangwill stated that the “conductors” of The New Witness would “do better to call it The False Witness.”[10] In 1920, Zangwill stated: “Yet in Mr. Chesterton’s own organ, The New Witness – the change of whose name to The False Witness I have already recommended – the most paradoxical accusations against the Jew find Christian hospitality.”[11]

In February 1921, in a letter to the editor of the Spectator, Zangwill described the proposal by Chesterton’s close friend, Hilaire Belloc, that Jews living in Great Britain should be characterised as a separate nationality, with special “disabilities and privileges,” as “ridiculously retrograde.”[12] Zangwill criticised Belloc’s scheme of “re-established Ghettos” in other articles, letters and notes in 1922. [13] Zangwill also observed in his letter to the Spectator, quite correctly, that Belloc’s “fellow-fantast, Mr. Chesterton, would revive the Jewish badge and have English Jews dressed as Arabs.”[12] This was a reference to a proposal by G. K. Chesterton in 1913 and again in 1920 that the Jews of England should be required to wear distinctive dress (he suggested the robes of an Arab).[14] According to Chesterton:

“But let there be one single-clause bill; one simple and sweeping law about Jews, and no other. Be it enacted, by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the Commons in Parliament assembled, that every Jew must be dressed like an Arab. Let him sit on the Woolsack, but let him sit there dressed as an Arab. Let him preach in St. Paul’s Cathedral, but let him preach there dressed as an Arab. It is not my point at present to dwell on the pleasing if flippant fancy of how much this would transform the political scene; of the dapper figure of Sir Herbert Samuel swathed as a Bedouin, or Sir Alfred Mond gaining a yet greater grandeur from the gorgeous and trailing robes of the East. If my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.”[15]

Whilst these letters and articles do not disprove the argument that Zangwill and Chesterton had an amicable relationship, at least for a time, they do suggest that Zangwill did not believe that Chesterton was guiltless of antisemitism. If Zangwill considered Chesterton a friend after 1915, let alone a pro-Jewish friend, he had a strange way of showing it. At the very least they problematize the argument that Chesterton could not have been antisemitic on the grounds that Zangwill was his friend, as from 1916 onwards Zangwill clearly came to perceive and describe Chesterton as an antisemite.

I would love to hear from anyone that has found any other evidence of a friendship or enmity between Zangwill and Chesterton (please click here to contact me).

Notes for the claim that Chesterton and the Anglo Jewish author Israel Zangwill were friends

[2] Joseph Pearce, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), p.446.

[3] Sean P. Dailey, “Tremendous Trifles,” Gilbert Magazine 12, no. 2&3 (November/December 2008), p.4. Gilbert Magazine is the periodical of the American Chesterton Society.

[5] See G. K. Chesterton, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1911), xi; Letter from G. K. Chesterton to the Editor, Jewish Chronicle, 16 June 1911, p.39; G. K. Chesterton, Our Notebook, Illustrated London News, 28 February 1914, p.322.

[6] According to Zangwill, Chesterton was “putting back the clock of philosophy even while he [was] putting forward the clock of drama. My satisfaction with the success of his play would thus be marred were it not that people enjoy it without understanding what Mr. Chesterton is driving at.” The letter is cited in G. K. Chesterton, Joseph McCabe, Hilaire Belloc, et al., Do Miracles Happen? (London: Christian Commonwealth, [1914]), p.23. The letter is also quoted by Joseph Pearce in Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), p.205.

[7] See Joseph Pearce, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), pp.213-220 and Dudley Barker, G. K. Chesterton: A Biography (London: Constable, 1973), pp.226-230.

[8] Letter from Israel Zangwill to Frances Chesterton, 19 January 1915, ADD MS 73454, fol. 44, G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library, London.

[9] G. K. Chesterton, “Mr. Zangwill on Patriotism,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 18 October 1917, pp.586-587.

[11] Israel Zangwill, “The Jewish Bogey (July 1920),” in Maurice Simon, ed., Speeches, Articles and Letters of Israel Zangwill (London: Soncino Press, 1937), p.103.

[12] Letter from Israel Zangwill to the Editor, “Problems of Zionism,” Spectator, 26 February 1921, p.263. In this letter, he went on to state that the so-called Jewish problem does “not concern Mr. Belloc, and I would respectfully suggest to him to mind his own business.” See also “Mr. Zangwill and Zionism,” Jewish Guardian, 4 March 1921, p.1.

[13] In May 1922, Zangwill referred to Belloc on a couple of occasions whilst criticising a non-territorial “spiritual” Zionism. He stated in the Jewish Guardian that “what the victims of anti-Semitism (the unassorted or downtrodden of our race) require is not a spiritual Zion, which ‘is no more a solution of the Jewish problem than Mr. Belloc’s fantastic scheme of re-established ghettos,’ but a ‘solid, surveyable territory.’” See “The Degradation of Zionism,” Jewish Guardian, 12 May 1922, p.8. He made similar remarks in a letter to the editor of the Times newspaper on 8 May 1922. He also wrote twenty-five pages of unpublished notes and criticisms of Belloc’s book, The Jews (1922).

G. K. Chesterton and the Dreyfus Affair

In 1899, Chesterton wrote a poem entitled “To a Certain Nation” as a reproach to France for the injustice done to Captain Dreyfus.[1] However, Chesterton soon reversed his opinion. In 1906, Chesterton added a note to the second edition of The Wild Knight which reveals that by 1906 he had started to change his position about where the greater injustice lay. The note stated that whilst “there may have been a fog of injustice in the French courts; I know that there was a fog of injustice in the English newspapers.” According to the note, he was unable to reach a “proper verdict on the individual,” which he largely attributed to the “acrid and irrational unanimity of the English Press.”[2] Chesterton maintained this antipathy about Dreyfus throughout his life. In letters to The Nation in 1911, Chesterton referred to the Jew “who is a traitor in France and a tyrant in England,” and stated that in “the case of Dreyfus,” he was quite certain that “the British public was systematically and despotically duped by some power – and I naturally wonder what power.”[3] He argued in 1928 that Dreyfus may or may not have been innocent, but that the greater crime was not how he had been treated at trial but how the English newspapers buried the evidence against him. According to Chesterton, “the English newspapers incessantly repeated that there was no evidence against Captain Dreyfus. They then cut out of the reports the evidence that he had been seen in German uniform at the German manoeuvres; or that he had obtained a passport for Italy and then gone to Germany.” Chesterton stated that when he discovered this, “something broke inside my British serenity; and a page of print has never been the same to me again.”[4] In another article Chesterton did defend a Jew, Oscar Slater, from the charge of murder, thereby demonstrating that Chesterton was not unremittingly antisemitic. However, seemingly unwilling to defend one Jew without sniping at another, he again repeated the accusation that the English newspapers left out “evidence that Dreyfus had appeared in German uniform at the German manoeuvres”[5] In another article, this time published in 1933, he criticised Hitler and Nazi antisemitism (something he did on a number of occasions as his defenders have pointed out), whilst yet again asserting that the English “were never told, for instance, that Dreyfus had got leave to go to Italy and used it to go to Germany; or that he was seen in German uniform at the German manoeuvres.”[6]

Chesterton’s unfavourable presentation of Captain Dreyfus can also be seen in one of his fictional works: “the Duel of Dr. Hirsch.” In this Father Brown short story, originally published in 1914, the Jew, Dr. Hirsch/Colonel Dubosc, is modelled on a diabolic composite of Judas Iscariot, Captain Dreyfus, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The Jew in the story sets up a second Dreyfus affair using false evidence, playing simultaneously the role of the accused villain (Hirsch) and the accusing hero (Dubosc). Hirsch succeeds in his complex scheme to be vilified as a traitor who has given military secrets to the Germans (the accuser being his own alter-ego), and then vindicated and heralded as a hero (whilst his alter-ego slinks away). Bryan Cheyette observes that Father Brown – a reoccurring hero in many of Chesterton’s short stories, who, as Dale Ahlquist has observed, reflects “Chesterton’s own moral reasoning” – “admits to being morally confused over whether Hirsch is guilty and compares it with his ‘puzzle’ over the ‘Dreyfus case.’” [7]

At the end of “the Duel of Dr. Hirsch,” the Jewish villain is seen by Father Brown’s assistant (M. Hercule Flambeau), half way through his metamorphosis from Colonel Dubosc to Dr. Hirsch. According to the narrator of the story, Hirsch’s face, with its “framework of rank red hair,” looked like “Judas laughing horribly and surrounded by capering flames of hell.” This final image of Hirsch is reminiscent of the so-called “diabolist” that Chesterton claimed he once knew, with “long, ironical face … and red hair,” and when seen in the light of the bonfire, “his long chin and high cheek-bones were lit up infernally from underneath; so that he looked like a fiend staring down into the flaming pit.”[8]

In conclusion, it does seem, on the surface, that the Dreyfus Case was a significant turning-point in Chesterton’s discourse about Jews (from sympathetic in 1899 to hostile by 1906). He claimed in 1928 that the Dreyfus Case marked “a great date in [his] life.” He stated that: “it was the last time I was deceived. Up to the time of the Dreyfus Case, I had believed like a child, or like a great mass of the public, that our press merely recorded what really happened; that no journalist but a chance criminal would suppress a vital fact.” It thus seems, as Julia Stapleton has rightly noted, that it never occurred to Chesterton to question whether there was any truth in the highly dubious allegations that Dreyfus was seen “in German uniform at the German manoeuvres,” or whether the claims “were suspect and thus beyond the realms of responsible journalism.” [9]

.

Notes for G. K. Chesterton and the Dreyfus Affair

[4] G. K. Chesterton, “Dreyfus and Dead Illusions,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 25 February 1928, 993.

[5] G. K. Chesterton, “In Defence of a Jew,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 27 August 1927, 575.

[6] G. K. Chesterton, “The Horse and the Hedge,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 30 March 1933, 55.

[7] G. K. Chesterton, “The Duel of Dr. Hirsch,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Complete Father Brown Stories (London: Wordsworth Classics, 2006), 213-224; Bryan Cheyette, Constructions of “the Jew” in English Literature and Society: Racial Representations, 1875-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 192-193; Dale Ahlquist, G. K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003), 166.

[8] G. K. Chesterton, “The Duel of Dr. Hirsch,” 224; G. K. Chesterton, “The Diabolist,” Daily News, 9 November 1907, 6.

[9] G. K. Chesterton, “Dreyfus and Dead Illusions,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 25 February 1928, 993; Julia Stapleton, Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G. K. Chesterton (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2009), 46.

The resilient myth that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism

A popular defence of G. K. Chesterton is that he could not have been an antisemite because the Wiener Library, one of the UK’s key institutes dedicated to researching antisemitism and the Holocaust, has defended him from the charge. Michael Coren instituted this defence in The New Statesman in 1986. He stated that the “Wiener Institute, the best monitors of anti-semitism in Britain, does not regard Chesterton as a culprit.”[1] Three years later, Coren attributed the following statement to the Wiener Library:

“The difference between social and philosophical anti-semitism is something which is not fully understood. … With Chesterton we’ve never thought of a man who was seriously anti-semitic on either count. He was a man who played along, and for that he must pay a price; he has, and has the public reputation of anti-semitism. He was not an enemy, and when the real testing time came along he showed what side he was on.”[2]

Coren did not provide a source for this alleged statement so it is not clear whether it was intended as an official or unofficial position of the Library. The Wiener Library informed me that “since the name of the person is not given, we can only suppose it to be an invention or else someone who was not entitled to talk, officially or unofficially, on the Library’s behalf.”[3]

Ben Barkow, the director of the Wiener Library, reported in 2010 that “numerous websites cite a made-up quotation by the Library stating that Chesterton was not antisemitic. Our efforts to have these false attributions removed have largely failed.”[4] The same issue of the Wiener Library News contained a short report (by the present author) on this Wiener Library Defence.[5]

Wiener Library News, Winter 2010, Issue 61. Front cover and pages 2 and 10 (click on images to zoom in)

Significantly, in an article published in 1963 about antisemitism, the Wiener Library Bulletin did make a brief statement about Chesterton, but only to report that “no Briton, least of all a Catholic, will feel pride in the obsessions of G. K. Chesterton.”[6]