Home » Posts tagged 'Sainthood'

Tag Archives: Sainthood

Ian Ker on G. K. Chesterton’s so-called “Semitism”

Ian Ker’s biography of G. K. Chesterton, published in 2011, seems to be widely regarded as the most comprehensive study of Chesterton to date. It is therefore instructive to see how Ian Ker deals with the accusation that Chesterton was antisemitic. Employing Chesterton’s own words, Ker notes that Chesterton and his friends (i.e. Hilaire Belloc and the staff at the New Witness) were often rebuked for “so-called ‘Anti-Semitism’; but it was ‘always much more true to call it Zionism.’” And this would seem to be the main basis for Ker’s defence of Chesterton, the argument that he was not antisemitic because he sympathised with Zionism. Chesterton’s sympathy for Zionism soon waned, and by 1925 his editorials in G.K.’s Weekly were ambivalent if not deprecating towards Zionism (link for more on this). Putting aside the fact that Chesterton’s so-called Zionism largely evaporated in the mid-1920s, the very reasons given for his support of Zionism serve to further demonstrate Chesterton’s distorted views about Jews. Again defending Chesterton and his friends in Chesterton’s own words, Ian Ker argues that the substance of “their ‘heresy’” was “in saying that Jews are Jews; and as a logical consequence that they are not Russian or Roumanians or Italians or Frenchmen or Englishmen.” Ker notes that Chesterton pointed out that his Zionism was based on “the theory that any abnormal qualities in the Jew”, such as being “traders rather than producers” and “cosmopolitans rather than patriots”, are “due to the abnormal position of the Jews.” The claims that “the Jew” has “abnormal qualities” (even if “the Jew” is patronisingly excused rather than blamed for having these abnormal qualities), and that he or she cannot really be English, French, German or Italian, and neither contributes nor feels patriotism for the countries within which he or she lives – views that I am confident Ian Ker does not share with Chesterton – are not just deprecating (so much for the Jews who fought and died for their countries during the First and Second World Wars), but also rooted in pervasive anti-Jewish myths and stereotypes. And yet Ker seems to agree with Chesterton that his “Zionism” was “Semitism” rather than “Anti-Semitism: “if that was ‘Anti-Semitism’, then Chesterton was an ‘Anti-Semite’ – but it would seem more rational to call it Semitism.” I cannot help wondering, if someone was to make similarly unacceptable and bigoted claims about Catholics – and indeed the prejudiced claim was often made in England during the 19th century that Catholics were different, dangerous and disloyal (English Jews and Catholics both having to fight for their emancipation during the 19th century) – and argue that English Catholics should be encouraged to depart England for a Catholic country, and that those who choose to remain should be required to wear distinctive clothing, would Ian Ker regard such prejudiced statements as “Anti-Catholic” or “Catholic”. And if he concluded that they were Anti-Catholic, why is he happy to regard Chesterton’s views as “Semitism” rather than “Anti-Semitism”? In my mind, prejudices, whether anti-Catholic or anti-Jewish (or anti- any other cultural group), are simply unacceptable. See Ian Ker, G. K. Chesterton: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 419-420.

In fairness, Ian Ker does acknowledge that the history of persecutions and pogroms in Europe “should have made Chesterton more cautious in what he said about the Jews.” However, Ker then argues that there were “mitigating” circumstances that should be taken into account. He suggests that Chesterton made these statements after his “beloved brother had died in a patriotic war soon after being found guilty in a libel case brought by a Jewish businessman who had effectively corrupted politicians in the Marconi scandal” and also after “international finance, in which Jews were very prominent, had played a not inconsiderable part in leaving Germany only partially weakened by the Treaty of Versailles.” According to Ker: “When, then, Chesterton demands that any Jew who wishes to occupy a political or social position … ‘must be dressed like an Arab’ to make it clear that he is a foreigner living in a foreign country, we need to bear those factors in mind.” Putting aside the dubious stereotype of the corrupt Jewish plutocrat, there are other flaws in these so-called “mitigating” circumstances. Firstly, Chesterton stated that it was not just particular Jews – or Jews seeking to “occupy a political or social position” as Ker suggests – that should be made to “wear Arab costume”, but rather “every Jew must be dressed like an Arab”. Chesterton explained that: “If my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.” Secondly, Chesterton did not, as Ker suggests, wait until his brother’s death (in December 1918) or the Treaty of Versailles (signed in June 1919) to make these dubious claims. For example, exhibiting his prejudice and stereotypes about both Arabs and Jews, he had already argued that “our Jews” should be required to wear “Arab costume” in the pages of the New Witness in 1913. See Ian Ker, G. K. Chesterton: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 422-423. G. K. Chesterton, “What shall we do with our Jews?”, New Witness, 24 July 1913, 370; and G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, 1920), 227.

Referring to Zionism, Chesterton stated that: “For if the advantage of the ideal to the Jews is to gain the promised land, the advantage to the Gentiles is to get rid of the Jewish problem, and I do not see why we should obtain all their advantage and none of our own. Therefore I would leave as few Jews as possible in other established nations”. Jews leaving Europe was, Chesterton suggested, simply the best way to get rid of the so-called “Jewish Problem”. Chesterton’s defenders would seem to believe that this demonstrates Chesterton’s warm friendly sentiments to Jews, but as Owen Dudley Edwards quite rightly concluded in the Chesterton Review: “to say that a man wishes you and all your people to live somewhere else, is not to say that he likes you. It does mean that he doesn’t want to murder you, but if you call someone an anti-Semite you are not necessarily calling him a Hitler, real or potential.” See G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, 1920), 248; and Owen Dudley Edwards, “Chesterton and Tribalism,” Chesterton Review VI, no.1 (1979-1980), 37.

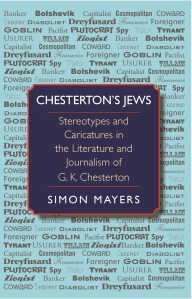

Chesterton’s Jews

G. K. Chesterton was a journalist and prolific author of poems, novels, short stories, travel books and social criticism. Prior to the twentieth century, Chesterton expressed sympathy for Jews and hostility towards antisemitism. He was agitated by Russian pogroms and felt sympathy for Captain Dreyfus. However, early into the twentieth century, he developed an irrational fear about the presence of Jews in Christian society. He started to argue that it was the Jews who oppressed the Russians rather than the Russians who oppressed the Jews, and he suggested that Alfred Dreyfus was not as innocent as the English newspapers claimed (click link for more on Chesterton and the Dreyfus Affair). His caricatures of Jews were often that of grotesque creatures dressed up as English people. His fictional and his non-fictional works repeated antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish greed and usury, bolshevism, cowardice, disloyalty and secrecy.

Available at: Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.de Amazon.fr

Many of Chesterton’s admirers fervently deny the presence of anti-Jewish hostility in his writings. Some of his defenders believe that Chesterton was an important figure within the Church, perhaps even a prophet or a saint. In fact, a growing number of people would like to see Chesterton canonised as a saint, and no doubt some are concerned that the accusation of antisemitism might prove an obstacle to such efforts. Since the publication of Chesterton’s Jews, the Bishop of Northampton, Peter Doyle, has appointed Canon John Udris to conduct an initial fact-finding investigation into the possibility of starting a cause for the canonisation of Chesterton. According to a report in the Catholic Herald on 3 March 2014, one of the reasons that the bishop selected Canon Udris for this investigation was that he has a “personal devotion to Chesterton,” and could thus be expected to put some “energy” into it. According to the report, referring to Chesterton’s argument that the Jews should be made to wear distinctive clothing so that everyone will know that they are “outsiders” (i.e. foreigners), Canon Udris observed that “you can understand why people make the assumption that he is anti-Semitic. But I would want to make the opposite case.” (Link for more on this canonisation investigation).

G. K. Chesterton’s “Daft” Suggestion: “Every Jew must be dressed like an Arab”

According to a report in the Catholic Herald on 3 March 2014, Canon John Udris, who has been appointed to conduct an initial fact-finding investigation into the possibility of starting a Cause for the canonization of G. K. Chesterton, observed that the accusation of antisemitism was the main obstacle to the Cause. According to the report, Canon Udris observed that “Chesterton said some ‘daft things’, including a suggestion that Jewish people should wear distinctive dress to indicate they were outsiders.” He concluded that: “You can understand why people make the assumption that he is anti-Semitic. But I would want to make the opposite case.” Mark Greaves, “G K Chesterton ‘breaks mould of conventional holiness’, says Cause investigator,” Catholic Herald (online), 3 March 2014.

The most notable instance of this “daft” suggestion – “quaint” but “quite serious” according to Chesterton – can be found in The New Jerusalem (1920). Chesterton argued that the Jews in England should be allowed to occupy any occupation but with one important stipulation: “But let there be one single-clause bill; one simple and sweeping law about Jews, and no other. Be it enacted, by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the Commons in Parliament assembled, that every Jew must be dressed like an Arab. Let him sit on the Woolsack, but let him sit there dressed as an Arab. Let him preach in St. Paul’s Cathedral, but let him preach there dressed as an Arab. It is not my point at present to dwell on the pleasing if flippant fancy of how much this would transform the political scene; of the dapper figure of Sir Herbert Samuel swathed as a Bedouin, or Sir Alfred Mond gaining a yet greater grandeur from the gorgeous and trailing robes of the East. If my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.” G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, [1920]), 227.

This was not the first time that Chesterton had suggested that Jews should be required to wear distinctive Arab clothing. In fact, Chesterton’s suggestion that all Jews should be legally required to wear distinctive “Arab costume” when in public was a part of his peculiarly Chestertonian construction of the Jew (exhibiting his caricatures and stereotypes about both Arabs and Jews). For example, in 1913, seven years prior to The New Jerusalem, he had already harked back to the Middle Ages for his solution to the so-called Jewish Problem. He observed that in the Middle Ages it was felt that the Jews, “whether they were nice or nasty, whether they were impotent or omnipotent… were different.” He noted that this recognition was expressed by “a physical artistic act, giving them a definite dwelling place and a definite dress.” This was a clear allusion to the ghetto and the Jew hat. Chesterton however had different ideas about appropriate though equally distinctive clothing. The Jews, he argued, should be required by law to “wear Arab costume.” “By all means let [a Jew] be Lord Chief Justice; but let him not sit in wig and gown, but in turban and flowing robes.” He observed that the “modern mood” is such that “I must advance it as a joke,” but he regarded it as a very real issue. He concluded that “if the Jew were dressed differently we should know what he meant; and when we were all quite separate we should begin to understand each other.” Similarly, in 1914, he stated in his regular column in the Illustrated London News, that the Jews may one day come to realize that they risk trading the faith of Moses and Isaiah for that of the Golden Image and the Market Place, and they may “wish they were sitting like an Arab in a clean tent in a decent desert.” G. K. Chesterton, “What shall we do with our Jews?”, New Witness, 24 July 1913, 370; G. K. Chesterton, Our Notebook, Illustrated London News, 28 February 1914, 322.

G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of the Jewish Coward

The stereotype of the cowardly Jew, though less prominent than the greedy Jew and the Jewish Bolshevik stereotypes in his discourse, was another feature in Chesterton’s antisemitic construction of “the Jew.” He argued that bravery and patriotism were foreign to the Jewish makeup. This antisemitic stereotype appeared in particular in 1917 and 1918. For Chesterton, the virtues of bravery, chivalry and patriotism were intertwined. That the Jews did not share these “Christian” qualities was, Chesterton believed, a point that should be understood, even excused, but certainly recognised. In an article on 11 October 1917, he stated that he felt “disposed to gibbet the journalist at least as much as the Jew; for the same journalism that has concealed the Jewish name has copied the Jewish hysteria.” According to Chesterton, “at least the wretched ‘alien’ can claim that if he is scared he is also puzzled; that if he is physically frightened he is really morally mystified. Moving in a crowd of his own kindred from country to country, and even from continent to continent, all equally remote and unreal to his own mind, he may well feel the events of European war as meaningless energies of evil. He must find it as unintelligible as we find Chinese tortures.” Chesterton claimed that he was inclined to “the side of mercy in judging the Jews,” at least in comparison to certain newspaper “millionaires.” He argued that a Jew with a gold watch-chain “grovelling on the floor of the tube” was not as ugly a spectacle as the newspaper millionaires who multiply their “individual timidity in the souls of men as if in millions of mirrors.” Chesterton was willing to accept that there were rare and exceptional Jews who won medals for bravery, but he was not willing to concede this to more than a small number of Jews. Such Jews, he argued, were rare, and so they should be honoured not merely as “exceptionally heroic among the Jews,” but also as “exceptionally heroic even among the heroes.” Chesterton concluded that it “must have been by sheer individual imagination and virtue that they pierced through the pacifist materialism of their tradition, and perceived both the mystery and the meaning of chivalry.” G. K. Chesterton, “The Jew and the Journalist,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 11 October 1917, pp. 562-563.

When later quizzed by Leopold Greenberg, the proprietor-editor of the Jewish Chronicle and the Jewish World, on 14 June 1918, as to whether he himself had witnessed Jews cowering in tube stations, Chesterton admitted that he had not personally witnessed this, but he argued that it was a matter of common knowledge. In an article on 21 June 1918, he stated that “the problem of aliens in air-raids is a thing that everybody knows.” He suggested that he could hardly be expected to go looking “for Jews in the Tubes, instead of going about my business above ground.” Chesterton concluded that if his affairs had led him into the Tubes during an air raid, he would probably have seen what others have reported, and the editor of the Jewish Chronicle and the Jewish World would no doubt have “refused my testimony as he refused theirs.” Somewhat patronizingly, Chesterton “excused” the Jew of his so-called cowardice during air raids, attributing it to the “psychological effect of a Gotha on a Ghetto”. He explained that he himself had “defended the Jew so situated; comparing him for instance to a Red Indian who might possibly be afraid of fireworks, to which he was not accustomed, and yet not afraid of slow fires, to which he was accustomed.” G. K. Chesterton, At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 21 June 1918, pp. 148-149. See also “A Reckless Charge,” Jewish Chronicle, 14 June 1918, 4.

Whilst Chesterton claimed that he was inclined towards mercy in judging cowardice, he was utterly unprepared to tolerate “pacifism”. Articles in 1917 and 1918 suggested that pacifism elevated cowardice to an ideal and denigrated bravery as a vice. It is one thing, he argued, to “feel panic and call it panic,” quite another to “cultivate panic and call it patriotism.” Chesterton regarded “absolute pacifism and the denial of national service simply as morally bad, precisely as wife-beating or slave-owning are morally bad.” He directed some “words of advice” to the Jews. He stated that “in so far as you say that you yourself ought not to be made to serve in European armies, I for one have always thought you had a case; and it may yet be possible to do something for you, … If you say that you ought not to fight, at least we shall understand. If you say that nobody ought to fight, you will make everybody in the world want to fight for the pleasure of fighting you.” Referring to Jews, he stated that “if they talk any more of their tomfool pacifism to raise a storm against the soldiers and their wives and widows, they will find out what is meant by Anti-Semitism for the first time.” G. K. Chesterton, “The Jew and the Journalist,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 11 October 1917, pp. 562-563 and G. K. Chesterton, “The Grand Turk of Tooting,” Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 25 October 1917, pp.610-611.

The reality is that during the First and Second World Wars, Anglo-Jews signed up for the armed forces with great enthusiasm. Despite this, Chesterton was not alone in embracing this antisemitic stereotype. As Tony Kushner (1989), Professor of the History of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton (and director of the Parkes Institute), has rightly stated: “On pure statistical grounds there was again no basis for the Jewish war shirker image to come about. To explain its pervasive appeal one has, as usual, to examine the past Jewish stereotype. The most significant aspect in this respect was the combined image of the cowardly and non-physical Jew.” Kushner explains that “the combined image of Jews as weak, cowardly, alien and powerful were all strongly ingrained in the public mind. Indeed the strength of such imagery is highlighted by the experience of Jews in the British Forces during the Second World War. As was the case in the 1914-18 conflict, a disproportionate number of Jews joined the Forces – 15% of Anglo-Jewry or 60,000 men and women compared to 10% of the population as a whole.” Tony Kushner, The Persistence of Prejudice: Antisemitism in British society during the Second World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), 122-123.

For more on this and other stereotypes and caricatures in Chesterton’s discourse, please see my recent book, Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G. K. Chesterton.

G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Jewish Bolshevik”

In a previous blog post I looked at the stereotype of the so-called greedy Jew in G. K. Chesterton’s fictional and journalistic discourse. In this blog post I will look at the stereotype of the “Jewish Bolshevik” in his discourse.

In his essay on G. K. Chesterton’s so-called “philosemitism,” William Oddie argues that Chesterton could not have been an antisemite because on a number of occasions he defended Jews from antisemitism [1]. William Oddie presented a diary entry, dated 5 January 1891, which stated that Chesterton felt so strongly about some vicious acts of cruelty to a Jewish girl in Russia that he was inclined to “knock some-body down”. He also quotes from letters by Chesterton’s alter-ego, Guy Crawford (under which name Chesterton published a series of letters). These were printed in the Debater, the magazine of the “Junior Debating Club,” in 1892. In these letters, Crawford discusses his plans to go to Russia to help “the Hebrews” suffering in pogroms. As William Oddie observed, the series of letters ends with “Guy Crawford” siding with a revolutionary mob in St. Petersburg, and leaping to the defence of a Jewish student. The student, who was killed in this fantastical account, was described by Crawford as “a champion of justice, like thousands who have fallen for it in the dark records of this dark land” [2]. These examples probably provide a fair reflection of Chesterton’s late teenage attitudes. However, his worldview, as with most people, changed over time. An example of his developing worldview can be seen in The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904). According to William Oddie, in this novel, Chesterton expressed “distaste for modernity and progress.” He quite rightly points out that this distaste was “a recent volte-face” [3]. This was not however the only volte-face in Chesterton’s worldview and discourse. He also changed his views about the Jews.

A relatively early and partial manifestation of this volte-face can be found in his novel, Manalive (1912), which reflected his worldview no less than the letters of Guy Crawford. According to the narrator of the story, “wherever there is conflict, crises come in which any soul, personal or racial, unconsciously turns on the world the most hateful of its hundred faces.” In the case of Moses Gould, the Jew in the novel, it was “that smile of the Cynic Triumphant, which has been the tocsin for many a cruel riot in Russian villages or mediaeval towns” [4]. As Cheyette has observed, the construction of the Jew as “innocent victim” seems to have been replaced in Manalive by the Russian Jew’s so-called “racial failure to go beyond his ‘cynical’ rationality” [5].

The transition from innocent victim in Russia to arch-cynic in Russia was only a partial volte-face. The complete volte-face would come later in the early 1920s, when Chesterton started to claim that the Jews were persecuting Russians. His narratives about the Jewish tyrant were intertwined with stereotypes about the Jewish Bolshevik. For example, in February 1921, Chesterton observed that there was once “a time when English poets and other publicists could always be inspired with instantaneous indignation about the persecuted Jews in Russia. We have heard less about them since we heard more about the persecuting Jews in Russia” [6]. He repeated this narrative about how it was once observed that it was the Jews who were persecuted in Russia, and now it is the Jews who persecute Russians, in What I Saw in America (1922). He stated that “we used to lecture the Russians for oppressing the Jews, before we heard the word Bolshevist and began to lecture them for being oppressed by the Jews” [7].

There were of course many Jews who were sympathetic towards Socialism and Bolshevism, just as there were many non-Jews who were sympathetic towards Socialism and Bolshevism. There were also many Jews who were antagonistic towards Bolshevism, and it was in no sense a Jewish movement. Chesterton did at least recognise that not all Jews were Bolsheviks, but he claimed that those who were not Bolsheviks were instead rich capitalists. Capitalism, he believed, was merely the other side of Communism. Despite acknowledging that not all Jews were Bolsheviks, he nevertheless painted a picture of Bolshevism as a specifically Jewish movement. For example, Chesterton stated in January 1921 that a study by H. G. Wells contained a “touch of an unreal relativity” when it came to “the Jewish element in Bolshevism.” Wells had observed that whilst many of the Russian exiles were Jewish, there were some who were not Jews. As he had on many other occasions, Chesterton conversely rejected the idea that Jews could be Russians. He clarified that the exiles were Jewish as there were “next to no real Russian exiles.” More significantly, he stated that “it is not necessary to have every man a Jew to make a thing a Jewish movement; it is at least clear that there are quite enough Jews to prevent it from being a Russian movement” [8]. He made a similar claim in August 1920: “There has arisen on the ruins of Russia a Jewish servile State, the strongest Jewish power hitherto known in history. We do not say, we should certainly deny, that every Jew is its friend; but we do say that no Jew is in the national sense its enemy” [9].

In June 1922, Chesterton expressed his hope that “some day there may be a little realism in the newspapers dealing with public life, as well as in the novels dealing with private life.” He stated that on that day, “we may hear something of the type that really is Bolshevist and generally is Jewish.” In addition to the type that becomes “an atheist from a vague idea that it is part of being a revolutionist,” there was “another type, less common but more clear-headed, who has really become a revolutionist only as part of being an atheist.” According to Chesterton, it was pointless to question this “special sort of young Jew” who exhorted the poor to attack the priest even though the priest was even poorer than they were, because “it was only in order to attack the priest that he ever troubled about the poor.” Chesterton concluded that this type of Jew “knows his own religion is dead; and he hates ours for being alive” [10].

Referring to Dr Oscar Levy, a prominent Jewish scholar of Nietzsche, Chesterton stated that: “He is a very real example of a persecuted Jew; and he was persecuted, not merely by Gentiles, but rather specially by Jews. He was hounded out of this country in the most heartless and brutal fashion, because he had let the cat out of the bag; a very wild cat out of the very respectable bag of the commercial Jewish bagman. He told the truth about the Jewish basis of Bolshevism, though only to deplore and repudiate it.” However, in response, Oscar Levy promptly wrote to Chesterton, pointing out that he was not driven out of England by Jews at all, and that the Jewish Chronicle and Jewish World had supported him against the decision by the Home Office. Furthermore, Levy argued that Bolshevism was more closely related to Christianity than to Judaism. The idea that the Anglo-Jewish community pulled the strings of the Home Office to arrange for Levy to be removed from Britain was simply a Bellocian and Chestertonian antisemitic invention [11].

Chesterton never abandoned the myth that Bolshevism was a Jewish movement. For example, whilst criticising “Hitlerism” in 1933, he asserted that the Jews “fattened on the worst forms of Capitalism; and it is inevitable that, on losing these advantages of Capitalism, they naturally took refuge in its other form, which is Communism. For both Capitalism and Communism rest on the same idea: a centralisation of wealth which destroys private property.” And referring to Jews in his autobiography, he stated that “Capitalism and Communism are so very nearly the same thing, in ethical essence, that it would not be strange if they did take leaders from the same ethnological elements” [12].

.

Notes for G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Jewish Bolshevik”

1. William Oddie, “The Philosemitism of G. K. Chesterton,” in William Oddie, ed., The Holiness of G. K. Chesterton (Leominster: Gracewing, 2010), 124-137.

2. William Oddie, “The Philosemitism of G. K. Chesterton,” 127-128; William Oddie, Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy: The Making of GKC, 1874-1908 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 80-81. The diary entry for 5 January 1891 can be found on page 24 of notebook (1890-1891), ADD MS 73317A, G. K. Chesterton Papers. The letters can be found in G. K. Chesterton [Guy Crawford, pseud.], “The Letters of Three Friends,” Debater III: no.13 (March 1892), 9-11; no.14 (May 1892), 27-29; no.17 (November 1892), 70-71. The letters were published in 1892, not 1891 as William Oddie suggests.

3. William Oddie, Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy: The Making of GKC, 1874-1908, 8.

4. G. K. Chesterton, Manalive (London: Thomas Nelson, 1912), 289.

5. See Bryan Cheyette, Constructions of “the Jew” in English Literature and Society: Racial Representations, 1875-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 192.

6. G. K. Chesterton, “The Statue and the Irishman,” New Witness, 18 February 1921, 102.

7. G. K. Chesterton, What I Saw in America (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1922), 142.

8. G. K. Chesterton, “The Beard of the Bolshevist,” New Witness, 14 January 1921, 22.

9. G. K. Chesterton, “The Feud of the Foreigner,” New Witness, 20 August 1920, 309. Chesterton shared this idea that Bolshevism was a Jewish movement with his close friend Hilaire Belloc. See Hilaire Belloc, The Jews (London: Constable, 1922), 167-185. See also Simon Mayers: The Catholic Federation, Hilaire Belloc, Antisemitism and Anti-Masonry

10. G. K. Chesterton, “The Materialist in the Mask,” New Witness, 30 June 1922, 406-407.

11. See G. K. Chesterton, “The Napoleon of Nonsense City,” G.K.’s Weekly, 14 August 1926, 388-389; Letter from Oscar Levy to the editor of G.K.’s Weekly, “Dr. Oscar Levy and Christianity,” G.K.’s Weekly, 13 November 1926, 126; Letter from Oscar Levy to the editor of G.K.’s Weekly, “Mr. Nietzsche Wags a Leg,” G.K.’s Weekly, 2 October 1926, 44-45. For more on Chesterton and Oscar Levy, see the following blog post, “A look at G. K. Chesterton and Oscar Levy on the ‘169th birthday’ of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche”

12. G. K. Chesterton, “The Judaism of Hitler,” G.K.’s Weekly, 20 July 1933, 311 and G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1936), 76.

G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Greedy Jew”

Prior to the twentieth century, G. K. Chesterton expressed sympathy for Jews and hostility towards antisemitism. He was agitated by Russian pogroms and felt sympathy for Captain Dreyfus. However, early into the twentieth century, he started to fear the presence of Jews in Christian society. He started to argue that it was the Jews who oppressed the Russians rather than the Russians who oppressed the Jews, and he suggested that Dreyfus was not as innocent as the English newspapers claimed (click link for more on Chesterton and Dreyfus). His caricatures of Jews were often that of grotesque creatures dressed up as English people. His fictional and his non-fictional works repeated antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish greed, usury, capitalism, bolshevism, cowardice, disloyalty and secrecy (each of these stereotypes are examined in detail in my recent book, Chesterton’s Jews). In this blog post, I will briefly examine Chesterton’s stereotype of the greedy usurious Jew.

G. K. Chesterton

It has been argued by a number of Chesterton’s defenders that if Chesterton did harbour ill will towards Jews, then it was only to particular Jews (such as Rufus and Godfrey Isaacs), that it was only subsequent to the notorious Marconi affair, and that it faded after a few years. Chesterton’s stereotyping of the greedy usurious Jew did not in fact revolve around the Marconi Affair and was not confined to particular individuals. His antisemitic stereotype of the greedy Jew can be partly traced to his idealisation of the Middle Ages and his critique of modernity. Chesterton traced many of the problems of modernity back to the Reformation, which he suggested tore Europe apart faster than the Catholic Church could hold it together [1]. He was romantically attracted to the Middle Ages, which he imagined to be a relatively well-ordered period in history, with happy peasants, Christianity as a healthy part of every-day life, and the trades managed equitably and protected by the Church and the guild system. The medieval guilds, he suggested, prevented usury from disrupting the balance of society and destroying the livelihood of the peasantry.

The usurers and plutocrats that Chesterton had in mind were Jewish. In his A Short History of England, published in 1917, Chesterton implied that the Jews were not as badly treated in the Middle Ages as often portrayed, though they were sometimes handed over to “the fury of the poor,” whom they had supposedly ruined with their usury [2]. In order to obtain the vast sums demanded by King John in the early thirteenth century, Jews were arrested, property seized, some Jews were hanged, and one Jew had several teeth removed to persuade him to pay the sums demanded. Even poor Jews had to pay a tax or leave the kingdom [3]. However, according to Chesterton, the idea that Jews were compelled to hand over money to King John or have their teeth pulled was a fabrication: “a story against King John” rather than about him. He suggested that the story was “probably doubtful” and the measure, if it was enacted, was “exceptional.” The Christian and the Jew, he claimed, had “at least equal reason” to view each other as the ruthless oppressor. “The Jews in the Middle Ages,” he asserted, were “powerful,” “unpopular,” “the capitalists of the age” and “the men with wealth banked ready for use” [4].

Chesterton repeated a similar narrative about King John (and Richard Lion-Heart) in his newspaper, the G.K.’s Weekly: “John Lackland, as much as Richard Lion-Heart, would have felt that to be in an inferior and dependent position towards Isaac of York for ever was utterly intolerable. A Christian king can borrow of the Jews; but not settle down to an everlasting compromise, by which the Jews are content to live on his interest and he is content to live on their clemency” [5].

According to Chesterton, “medieval heresy-hunts spared Jews more and not less than Christians” [6]. A reoccurring hero in many of Chesterton’s short stories was Father Brown. Dale Ahlquist (2003), one of Chesterton’s staunch defenders, observes that Father Brown and Chesterton share the same “moral reasoning” [7]. This would seem to be confirmed in “The Curse of the Golden Cross” (1926). In this story, Father Brown, like Chesterton, argued that it was a myth that Jews were persecuted in the Middle Ages: “‘It would be nearer the truth,’ said Father Brown, ‘to say they were the only people who weren’t persecuted in the Middle Ages. If you want to satirize medievalism, you could make a good case by saying that some poor Christian might be burned alive for making a mistake about the Homoousion, while a rich Jew might walk down the street openly sneering at Christ and the Mother of God’” [8].

In The New Jerusalem (1920), Chesterton again argued that Jews were inclined to usurious practices. It was not just the Jews that he caricatured. He also repeated stereotypes about “gypsy” (or sometimes “gipsey” in Chesterton’s parlance [9]) pilfering and kidnapping (link for more on Chesterton and the stereotype of the child-kidnapping “gypsy”). He suggested that a comparison may be made between “Gipsey pilfering” and “Jewish usury.” Both “races,” he observed, “are in different ways landless, and therefore in different ways lawless.” Chesterton referred to the pilfering of chickens by “gypsies”, and the kidnapping of children, which he correlated to Jewish usury and fencing. He outlined his case as follows: “It is unreasonable for a Jew to complain that Shakespeare makes Shylock and not Antonio the ruthless money-lender; or that Dickens makes Fagin and not Sikes the receiver of stolen goods. It is as if a Gipsey were to complain when a novelist describes a child as stolen by the Gipseys, and not by the curate or the mothers’ meeting. It is to complain of facts and probabilities.” He concluded that “there may be good Gipseys” and “good qualities which specially belong to them as Gipseys.” “Students of the strange race,” he observed, have even “praised a certain dignity and self respect among the women of the Romany. But no student ever praised them for an exaggerated respect for private property, and the whole argument about Gipsey theft can be roughly repeated about Hebrew usury” [10].

The problem of the wandering Jewish financier, Chesterton suggested, was not confined to Europe. He argued in G.K.’s Weekly that America was the new pied a terre of the international Jewish financier, and that it was for the sake of such Jews that Britain has “clung to the American skirts” [11]. The stereotype of the greedy plutocratic Jew can also be found in Chesterton’s short stories and novels. For example, at the conclusion of “The Bottomless Well,” Horne Fisher, the detective protagonist of the story, engages in a diatribe against the Jews. “It’s bad enough,” he observed, “that a gang of infernal Jews should plant us here, where there’s no earthly English interest to serve, and all hell beating up against us, simply because Nosey Zimmern has lent money to half the Cabinet.” He went on to state: “But if you think I am going to let the Union Jack go down and down eternally like the Bottomless Well, down into the blackness of the Bottomless Pit, down in defeat and derision amid the jeers of the very Jews who have sucked us dry – no, I won’t, and that’s flat; not if the Chancellor were blackmailed by twenty millionaires with their gutter rags, not if the Prime Minister married twenty Yankee Jewesses” [12]. Another story, “The Five of Swords,” revolves around cowardly Jewish moneylenders who ruin and murder their victims [13].

One question that may be asked is what led Chesterton to embrace this and other antisemitic stereotypes. One possible answer is that his closest friend, Hilaire Belloc, convinced him of their veracity. Chesterton and Belloc met in 1900. By 1904, Chesterton was working with Belloc on his novel Emmanuel Burden (providing Belloc with a number of sketches for the characters in his novel, including the main antagonist, I. Z. Barnett, who is portrayed as a greedy, manipulative and fraudulent German Jew). In this novel, Barnett formulated a project, the “African M’Korio” scheme, which involved the manipulation of the stock market, the exploitation of Africa, and the destruction of Emmanuel Burden, a naïve but honest British merchant. It was not just in his fiction that Belloc constructed his image of exploitive Jews in Africa. In a letter to Chesterton in 1906, Belloc stated that he was “now out against all Vermin: notably South African Jews”. Significantly, it was around this time that Chesterton started to stereotype Jews in his own fiction – the earliest example being the cowardly and secretive Jewish shopkeeper in The Ball and the Cross, which was first published as a feuilleton in the Commonwealth in 1905/6. [14].

Hilaire Belloc

Another stereotype of “the Jew” that was prominent in Chesterton’s discourse (and shared by Belloc) was the Jewish Bolshevik. Chesterton often closely linked this stereotype to that of Jewish bankers, usurers and capitalists. He maintained that the rich Jewish capitalists and poor Jewish Bolsheviks were merely the other side of, if not closely associated and allied with, each other. He argued that “Big Business and Bolshevism are only rivals in the sense of making rival efforts to do the same thing; and they are more and more even doing it in the same way. I am not surprised that the cleverest men doing it in both cases are Jews.” According to Chesterton, the “whole point” of the New Witness was to maintain that “Capitalism and Collectivism are not contrary things. It is clearer every day that they are two forms of the same thing” [15]. The stereotype of the Jewish Bolshevik, which was almost as pervasive in Chesterton’s discourse as that of the greedy usurious Jew, will be examined in my next blog post on Chesterton (click here for link to G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Jewish Bolshevik”).

.

Notes for G. K. Chesterton and the Stereotype of “the Greedy Jew”

1. G. K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong with the World (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1910), 42.

2. G. K. Chesterton, A Short History of England (London: Chatto & Windus, 1917), 108-109.

3. Anthony Julius, Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 118-119, 643 fn.82-84.

4. G. K. Chesterton, A Short History of England (London: Chatto & Windus, 1917), 108-109.

5. G. K. Chesterton, “The Neglect of Nobility,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 4 August 1928, 327.

6. G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (London: Hutchinson, 1936), 76.

7. Dale Ahlquist, G. K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003), 166.

8. G. K. Chesterton, “The Curse of the Golden Cross,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Complete Father Brown Stories (London: Wordsworth Classics, 2006), 432. This short story was originally published in 1926.

9. The strange spelling of “gipsey” is Chesterton’s. The spelling has been changed in some later editions of The New Jerusalem.

10. G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson, [1920]), 232. An editorial in G.K.’s Weekly repeated the same stereotypes linking the so-called child-kidnapping “gypsy” with the usurious Jew. See G.K.’s Weekly, 2 May 1925, 126.

11. G. K. Chesterton, “Exodus from Europe,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 28 December 1929, 247.

12. G. K. Chesterton, “The Bottomless Well,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Other Stories (London: Cassell, 1922), 73.

13. G. K. Chesterton, “The Five of Swords,” in G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Other Stories (London: Cassell, 1922), 255-282.

14. See Hilaire Belloc, Emmanuel Burden (London: Methuen, 1904); Letter from Hilaire Belloc to G. K. Chesterton, February 1906, ADD MS 73190, fol. 14, G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library Manuscripts, London; G. K. Chesterton, “The Ball and the Cross,” Commonwealth: vol. 10, no. 3-12 (1905), and vol. 11, no. 1, 2, 4, 6, 11 (1906).

15. G. K. Chesterton, “Rothschild and the Roundabouts,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 17 November 1922, 309-310.

G. K. Chesterton and the Myth of the Child-Kidnapping “Gypsy”

It was reported in various newspapers yesterday (23/10/2013) that Irish police had seized a blonde-haired girl from a Roma family in Dublin. According to the report in the Times, “the blonde girl with blue eyes, believed to be aged seven, was taken from her Dublin home after a tip-off to police that she did not look like her parents or siblings, who have dark hair and complexions.” The report in the Times noted similarities with other recent cases. For example, it noted that police arrested a Roma woman in Greece in 2008 and accused her of kidnapping a blonde girl. DNA tests later proved that the Roma woman in Greece was the parent. According to Siobhan Curran, the co-ordinator of a Roma support project, “old stereotypes” are being resurrected that could lead to a “witch-hunt” [1].

According to a BBC news report today (24/10/2013), DNA tests have now proven that the blond girl in Dublin is the daughter of the Roma parents. A statement by An Garda Síochána (the Irish Police service) observed that “protecting vulnerable children is of paramount importance”. On the surface the statement seems reasonable enough. However, if tip-offs based on little more than children being blonde-haired are sufficient to lead to them being removed from their Roma parents by police, then Siobhan Curran’s concerns about old stereotypes and a witch-hunt are not without foundation [2].

Significantly, G. K. Chesterton, currently being investigated as a possible candidate for sainthood, also repeated this myth of the child-kidnapping “gypsy” (or “gipsey” in Chesterton’s parlance). He combined this anti-Roma myth with that of the anti-Jewish stereotype of the “Hebrew usurer”. According to Chesterton in The New Jerusalem: “It is absurd to say that people are only prejudiced against the money methods of the Jews because the medieval church has left behind a hatred of their religion. We might as well say that people only protect the chickens from the Gipseys because the medieval church undoubtedly condemned fortune-telling. It is unreasonable for a Jew to complain that Shakespeare makes Shylock and not Antonio the ruthless money-lender; or that Dickens makes Fagin and not Sikes the receiver of stolen goods. It is as if a Gipsey were to complain when a novelist describes a child as stolen by the Gipseys, and not by the curate or the mothers’ meeting. It is to complain of facts and probabilities. There may be good Gipseys; there may be good qualities which specially belong to them as Gipseys; many students of the strange race have, for instance, praised a certain dignity and self-respect among the women of the Romany. But no student ever praised them for an exaggerated respect for private property, and the whole argument about Gipsey theft can be roughly repeated about Hebrew usury.” [3]

The myth of the child-kidnapping “gypsy” who steals chickens and children (linked to a caricature of “the Jews”) can also be found in Chesterton’s newspaper. According to G.K.’s Weekly: “The idea of Zionism may be impossible, but it was certainly ideal. It consisted of the perfectly true conception that in the quarrel of Jews and Gentiles there had been faults on both sides. It is rather as if the authorities had gone to the race that we call Gypsies and said something like this, without the least malice or prejudice and with a desire for a settlement: ‘We think it is absurd of you to say that none of you ever steal chickens; and we suspect that there is some truth in the story that some of you stole children. On the other hand, we think it abominable that you should be knocked about from pillar to post, and hunted by landlords and magistrates, and we make a proposal. We will give you a great piece of common land where you often camp and build you houses there and hope we shall all be friends.’ That was the implication of Zionism; the world as a whole had some persecution to apologize for; the Jews as a whole had some usury and similar things to apologise for.” [4]

As Peter McGuire (lecturer in Irish Folklore at University College Dublin) reports, the child-kidnapping “gypsy”, like the ritual murdering Jew (another antisemitic myth that Chesterton seemed to embrace [5]), is a character from folktale. For centuries, Jews and Roma have both been branded as thieves, parasites, sorcerers, child-kidnapers and murderers. McGuire concludes, quite rightly, that it is sad but true that “societies are notoriously resistant to accept or even consider evidence which challenges the ancient prejudices expressed in folklore” [6]. The fact that Roma and Sinti continue to be vilified, and child-kidnapping folktales continue to circulate, testifies to the resilience and durability of such cultural myths and stereotypes.

.

Notes for G. K. Chesterton and the Myth of the Child-Kidnapping “Gypsy”

1. “Police seize blonde girl from Roma in Dublin,” The Times, 23 October 2013, p.5. Similar reports can be found in other English daily newspapers for 23 October 2013.

2. “DNA tests prove Dublin Roma girl is part of family,” BBC News Europe (link here).

3. G. K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1920), p.232. Page numbers in other editions may vary but the page can be found in chapter XIII. The strange spelling of “gipsey” is found in the Thomas Nelson and Sons 1920 edition of The New Jerusalem. Some later editions of The New Jerusalem have changed “gipseys” to “gipsies.”

4. [G. K. Chesterton], G.K.’s Weekly, 2 May 1925, p.126.

5. G. K. Chesterton and his brother Cecil Chesterton both believed that whilst the accusation could not be levelled at all Jews, some diabolic secret societies of Jews engaged in ritual murder. In 1914, in the New Witness, in response to the Beilis blood libel, Cecil Chesterton characterised Russian pogroms as something horrible, but also something to be understood as part of an ongoing “bitter historic quarrel” between the Jews and the Russians. The evidence, Cecil Chesterton argued, points to a “savage religious and racial quarrel.” He suggested that it was sometimes the “naturally kindly” Russians who were “led to perpetrate the atrocities,” and sometimes it was the “equally embittered” Jews, who, “when they got a chance of retaliating, would be equally savage.” Referring to the Beilis affair, he stated that: “An impartial observer, unconnected with either nation, may reasonably inquire why, if we are asked to believe Russians do abominable things to Jewish children, we should at the same time be asked to regard it as incredible … that Jews do abominable things to Russian children – at Kieff, for instance”. In response, Israel Zangwill, a prominent Anglo-Jewish author and playwright, wrote a letter to Cecil, rightly arguing that following Cecil’s flawed logic we should have to accept that if hooligans throttle Quakers then Quakers must also be throttling hooligans. In reply, Cecil Chesterton stated that no sane man would suggest that ritual murder was a religious rite of Judaism, but “there may be ferocious secret societies among the Russian Jews,” and “such societies may sanctify very horrible revenges with a religious ritual.” Cecil Chesterton also revived the anti-Jewish host desecration myth. He argued that in the case of Kieff, “the Jews may or may not have insulted the Host, as was alleged. I do not know. But I do know that they wanted to; because I know what a religion means, and therefore what a religious quarrel means” (Cecil Chesterton, “Israel and ‘The Melting Pot,’” New Witness, 5 March 1914, 566-567; Cecil Chesterton, “A Letter from Mr. Zangwill,” New Witness, 12 March 1914, 593-594). In 1925, G. K. Chesterton stated that “the Hebrew prophets were perpetually protesting against the Hebrew race relapsing into idolatry that involved such a war upon children; and it is probable enough that this abominable apostasy from the God of Israel has occasionally appeared in Israel since, in the form of what is called ritual murder; not of course of any representative of the religion of Judaism, but by individual and irresponsible diabolists who did happen to be Jews” (G. K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man, London: Hodder and Stoughton, [1925], 136). For more on this, see Simon Mayers, “From the Christ-Killer to the Luciferian: The Mythologized Jew and Freemason in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century English Catholic Discourse,” Melilah 8 (2011), pp.48-49. Melilah is the open access peer-reviewed journal of the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Manchester (link here).

6. Peter McGuire, “Do Roma ‘Gypsies’ Really Abduct Children?”, The Huffington Post, 24 October 2013 (link here).

G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc discussing Hitler and the Jews (1933-1937)

Some of G. K. Chesterton’s fervent defenders (especially those who would like to see him declared a saint) argue that he could never have been antisemitic because he was a staunch and early critic of Hitler. The argument that he could not have been antisemitic on the grounds that he criticised Hitler is weak and unsound. Interpreted in the very best light, it would only demonstrate that Chesterton, in the final years of his life, eventually overcame his anti-Jewish discourse. However, the evidence does not even support the conclusion that he overcome his antisemitic prejudice, for there is little to suggest that he actually altered or softened his opinions about Jews or the so-called “Jewish Problem” after Hitler rose to power in Germany. If anything, Chesterton considered his critiques of “Hitlerism” and Nazi antisemitism to be entirely consistent with his earlier deprecating stereotypes of the Jew and his proposed solutions to the Jewish Problem. As far as Chesterton was concerned, the rise of Hitlerism clarified the urgency of solving the so-called Jewish Problem. Significantly, he not only continued to maintain his antisemitic stereotypes of the Jew from 1933 onwards, he incorporated them into the very articles in which he condemned and criticised Hitlerism. So yes, he did say in an oft-quoted interview in 1933 that he was “quite ready to believe” that he and Belloc would “die defending the last Jew in Europe” (“Mr. G. K. Chesterton on Truculent Prussianism,” Jewish Chronicle, 22 September 1933, 14.) But then he also claimed in G.K.’s Weekly in July 1933 that “it is perfectly true that the Jews have been very powerful in Germany. It is only just to Hitler to say that they have been too powerful in Germany.” Chesterton argued that it will be very difficult for Hitler to persuade Germans to amputate the Jewish contributions to German culture, such as Heinrich Heine and Felix Mendelssohn. “But again,” he continued, “it is but just to Hitlerism to say that the Jews did infect Germany with a good many things less harmless than the lyrics of Heine or the melodies of Mendelssohn.” Chesterton went on to state that “it is true that many Jews toiled at that obscure conspiracy against Christendom, which some of them can never abandon; and sometimes it was marked not be obscurity but obscenity. It is true that they were financiers, or in other words usurers; it is true that they fattened on the worst forms of Capitalism; and it is inevitable that, on losing these advantages of Capitalism, they naturally took refuge in its other form, which is Communism” (G. K. Chesterton, “The Judaism of Hitler,” G.K.’s Weekly, 20 July 1933, 311).

G. K. Chesterton, “The Judaism of Hitler,” G.K.’s Weekly, 20 July 1933.

.

Chesterton repeated the antisemitic stereotype of rich greedy Jews in other articles that were critical of Hitler. For example, in an essay entitled “On War Books,” he condemned “Herr Hitler and his group” for “beat[ing] and bully[ing] poor Jews in concentration camps,” but then he stated that “what is even worse, they do not beat or bully rich Jews who are at the head of big banking houses” (G. K. Chesterton, “On War Books,” G.K.’s Weekly, 10 October 1935, 28). Interestingly, a later version of this essay, published posthumously in a volume entitled The End of the Armistice in 1940, omits the entire sentence in which Chesterton lamented that rich banking Jews escaped the beating and bullying (G. K. Chesterton, “On War Books,” in The End of the Armistice, edited by Frank Sheed, London: Sheed & Ward, 1940, 192). Presumably the decision to remove the offensive sentence was made by Frank Sheed, the volume’s editor and publisher.

Chesterton repeated the stereotype of the pro-German Jew in his critique of Hitler. He asked, “was Hitler really so ignorant, that he did not know that the Jews were the prop of the Pro-German cause throughout the world?” (G. K. Chesterton, “A Very Present Help,” G.K.’s Weekly, 4 May 1933, 135). Chesterton criticised Hitler, and then repeated his claim that there is a Jewish Problem. He stated that “there is a Jewish problem; there is certainly a Jewish culture; and I am inclined to think that it really was too prevalent in Germany. For here we have the Hitlerites themselves, in plain words, saying they are a Chosen Race. Where could they have got that notion? Where could they even have got that phrase, except from the Jews?” (G. K. Chesterton, “A Queer Choice,” G.K.’s Weekly, 29 November 1934, 207).

Chesterton’s criticisms of Dreyfus and the Dreyfusards, which he often repeated throughout his journalistic career (link for G. K. Chesterton and the Dreyfus affair), were also repeated in his critiques of Hitler. He stated in March 1933 that when England “wanted to abuse France, where there is really very little real Anti-Semitism, we turned the world upside about the condemnation of one isolated individual Jewish officer, who had attained a high position of confidence, and who was charged, rightly or wrongly, with violating that confidence.” Chesterton combined criticising the Germans for persecuting Jews with repeating his earlier assertions that Dreyfus was probably a Germany spy. According to Chesterton, the English were never informed that “Dreyfus had got leave to go to Italy and used it to go to Germany; or that he was seen in German uniform at the German manoeuvres.” Chesterton criticised Hitler for persecuting ordinary Jews, and then observed that in the case of Dreyfus, the “particular Jew in France may or may not have been a traitor; but at least he was tried for being a traitor” (G. K. Chesterton, “The Horse and the Hedge,” G.K.’s Weekly, 30 March 1933, 55). As Julia Stapleton has rightly noted, it seems that it never occurred to Chesterton to question whether there was any truth in the highly dubious allegations that Dreyfus was seen “in German uniform at the German manoeuvres,” or whether the claims “were suspect and thus beyond the realms of responsible journalism” (Julia Stapleton, Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G. K. Chesterton, Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2009).

Chesterton also sometimes defended Hitler as if he were a mere puppet or “tool”. In September 1934, he stated that “I may possibly cause some surprise, if I conclude the composite portrait by saying that in certain aspects, and under certain limitations, I do not believe that Hitler is altogether a bad fellow; and that he is almost certainly a much better fellow than the men who are going to use him.” Chesterton suggested that in the beginning “he did really intend to do something for the poor, and especially for the peasants.” If he “did not do enough for his better ideas, and later did much more for his worst ones,” Chesterton argued, then “the reason is quite simply that he is not the Dictator.” He concluded that Hitler’s puppeteer or “drill-sergeant” will “soon give him his marching orders again” (G. K. Chesterton, “The Tool,” G.K.’s Weekly, 6 September 1934, 8-9). He repeated this idea in March 1936, when Hitler ordered the occupation of the Rhineland in contravention of the Versailles treaty. Chesterton stated that: “I have always said that there were healthy elements in Hitlerism, and even in Hitler; indeed I rather suspect that Hitler is one of the healthy elements in Hitlerism.” Chesterton argued that Hitler was “a better man than the men around him or behind him” (G. K. Chesterton, “Why did he do it?”, G.K.’s Weekly, 26 March 1936, 18).

As previously mentioned, Chesterton did say in an interview in 1933, that he was “quite ready to believe” that he and his close friend Hilaire Belloc would “die defending the last Jew in Europe”. Like Chesterton, Belloc did criticise Nazism. Chesterton and Belloc were also both staunch critics of the eugenics movement – though Chesterton’s book on eugenics included caricatures of Jews (See G. K. Chesterton, Eugenics and Other Evils, London: Cassell and Company, 1922; “Hilaire Belloc and the Ministry of Health,” Catholic Federationist, September 1920, 6). However, also like Chesterton, Belloc’s defence of Jews was somewhat equivocal. In his third edition of The Jews published in 1937, Belloc framed the problem of the Nazi persecution of Jews as one primarily of efficacy in solving the so-called “Jewish Problem”. Belloc asked what effect Nazi policy would “have upon a solution of the Jewish question?” “Is it,” he asked, “an advance towards a just solution of that question or not?” He observed that “there is no doubt that the Nazi attack was sincere” and that “there is no doubt that in the eyes of its authors it was provoked by a situation which they thought intolerable.” But the “Nazi attack”, he concluded, could be “neither thorough nor final.” Belloc argued that “it is not immoral, to declare a new policy and to say, ‘we will in future regard Jews as citizens of a different class from those around them, their hosts.” However, he concluded that the attack was unjust because “when things of that kind are done, justice demands that the effect shall be gradual, and that the loser by any new regulation shall be compensated.” It seems however that the main point of contention for Belloc was not that the Nazi policy was unjust, but that it was a failed policy. “The Nazi attack upon such of the Jewish race as are subject to Berlin is,” Belloc concluded, “not thorough, not final, but incomplete, and I think soon to prove abortive.” According to Belloc, “the policy has missed its mark, on lower grounds: it has missed its mark, because it has not dared to be thorough and has not had the competence to be well thought out” (Hilaire Belloc, The Jews, third edition, London: Constable, 1937, xxxix- xliii).

At best these essays by G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc reveal an ambivalent sentiment about Jews (which is to say, thinly veiled antipathy towards Jews, combined with equivocal defences of them). They were more an attack on what Chesterton referred to as “truculent Prussianism”, and an equivocal criticism of Hitler, than a defence of Jews. And this was the period in which, according to his defenders, Chesterton’s discourse about Jews was at its most sympathetic.

For more about G. K. Chesterton’s antisemitism, see: Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G. K. Chesterton

“Ludicrous, surreal” defence of G. K. Chesterton

A few days ago, Michael Coren reported a so-called “ludicrous, surreal episode” [1]. The episode in question was a Twitter discussion about a claim made in one of his books that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism. From the language employed, one might imagine a particularly bitter exchange, for Coren uses phrases such as the following to describe – and presumably to deter – those who dare to criticise Chesterton: “monomania, wrapped in the last acceptable prejudice of anti-Catholicism,” “the fundamentalism of those so committed to damaging Chesterton’s reputation,” and “the most extreme, bizarre lengths to have their way” [1]. The ad hominem tactic of dismissing out of hand the critics of Chesterton as “anti-Catholic” is regrettable and unfounded (especially as the discussion in question focused on Chesterton and the Wiener Library and not Chesterton’s Catholicism). Speaking for myself, I harbour no hostility for Catholics or Catholicism, and my concerns about Chesterton end with his hostile stereotypes and caricatures (about Jews and other “Others”). If I harbour a prejudice it is – to use a phrase once used by Chesterton to describe the sentiments of Americans – “a prejudice against Anti-Semitism; a prejudice of Anti-Anti-Semitism” [2].

But back to the article. Coren points out that he devoted a chapter to the issue of Chesterton’s discourse about Jews, and that only “one brief passage concerned London’s Wiener Library, a small institution devoted to the study of the Holocaust and anti-Semitism.” He stated that: “I spent a morning there in 1985 and discussed my research with a librarian. He told me that Chesterton was never seriously anti-Semitic. ‘He was not an enemy, and when the real testing time came along he showed what side he was on.’” Coren then expresses his indignation that “a self-published writer in Britain” – a reference to my recent examination of Chesterton’s stereotyping in Chesterton’s Jews – “demanded a name, proof, a reference.” “Sorry, mate: no name, no proof, and it was, as I say, a quarter of a century ago,” Coren replies. [1]

If Coren had originally stated merely that he had discussed his research with “a librarian” and that this librarian had defended Chesterton, then this would indeed be a relative non-issue (though a source citation would still have been useful). However, in the New Statesman in 1986 he attributed the defence of Chesterton to “the Wiener Institute” [3]. And in his biography of Chesterton the statement in defence of Chesterton is attributed to “the Wiener Library” [4]. There is of course a world of difference between the personal sentiment of an unnamed librarian and the position of the Wiener Library. Interestingly, he now describes the Wiener Library as “a small institution,” whereas back in 1986 when he was citing the Wiener Library in defence of Chesterton, he described the Wiener Library as “the best monitors of anti-semitism in Britain” [3].

The real issue is not Coren’s book per se – as he acknowledges, there have been plenty of subsequent biographies of Chesterton, and “some of them, frankly, rather better” than his [1]. However, subsequent authors have taken Coren’s earlier claim that the Wiener Library defended Chesterton at face value, and have repeated it in books, articles and web sites. As Ben Barkow, the current director of the Wiener Library states, “numerous websites cite a made-up quotation by the Library stating that Chesterton was not antisemitic. Our efforts to have these false attributions removed have largely failed” [5]. As a result, the myth that the Wiener Library defends Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism has acquired currency, when according to Coren’s latest article, he only discussed his research with an unnamed librarian he once met there [1] [6].

Turning to Coren’s other main point, he observes that Chesterton was “an early anti-Nazi” [1]. Here Coren is on safer – which is not to say solid – ground, and many of Chesterton’s defenders make the same point. Chesterton was anti-Nazi and it would be unfair to equate his particular brand of anti-Jewish discourse with Nazi antisemitism. However, if we are going to be fair and balanced, we should also point out that often in the very same articles in which Chesterton criticised Nazi antisemitism, he also repeated the stereotypes and caricatures of Jews that he had maintained before the 1930s. His defence of Jews was therefore not without its equivocation. Let’s look at a few examples. In March 1933, he criticised Hitler’s antisemitism, but then repeated his old claim that the English were never allowed to hear that “Dreyfus had got leave to go to Italy and used it to go to Germany; or that he was seen in German uniform at the German manoeuvres” [7]. In July 1933, he criticised “Hitlerism”, but then observed that it was “only just to Hitler” to point out that the Jews “have been too powerful in Germany.” He stated that “it is but just to Hitlerism to say that the Jews did infect Germany with a good many things less harmless than the lyrics of Heine or the melodies of Mendelssohn. It is true that many Jews toiled at that obscure conspiracy against Christendom, which some of them can never abandon; and sometimes it was marked not be obscurity but obscenity. It is true that they were financiers, or in other words usurers; it is true that they fattened on the worst forms of Capitalism; and it is inevitable that, on losing these advantages of Capitalism, they naturally took refuge in its other form, which is Communism” [8]. In November 1934, he criticised “the Hitlerites”, but then stated that: “There is a Jewish problem; there is certainly a Jewish culture; and I am inclined to think that it really was too prevalent in Germany. For here we have the Hitlerites themselves, in plain words, saying they are a Chosen Race. Where could they have got that notion? Where could they even have got that phrase, except from the Jews?” [9]. (For more on Chesterton’s discourse about Hitler and the Jews, see G. K. Chesterton discussing Hitler and the Jews, 1933-1936).

Coren concludes that he would rather be in the “valley with Gilbert than the peak with his critics,” because according to Chesterton it is possible to see “only small things from the peak” [1]. If viewing Chesterton’s discourse from the valley means missing such “small” details as these, then I am happy to occupy “the peak with his critics.”

.

Notes for “Ludicrous, surreal” defence of G. K. Chesterton

1. Michael Coren, “‘Ludicrous, surreal episode’ against G. K. Chesterton returns,” The B.C. Catholic, 13 September 2013, http://bcc.rcav.org/opinion-and-editorial/3069-canonization-attempt-resurrects-anti-semitic-claim (downloaded 17 September 2013).

2. G. K. Chesterton, What I Saw in America (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1922), 140-142.

3. Michael Coren, “Just bad friends,” review of G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, by Michael Ffinch, New Statesman, 8 August 1986, 30.

4. Michael Coren, Gilbert: The Man Who Was G. K. Chesterton (London: Jonathan Cape, 1989), 209-210.

5. Ben Barkow, “Director’s Letter,” Wiener Library News, Winter 2010, 2.

6. For an examination of this resilient myth, see Simon Mayers, “The resilient myth that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism,” 1 September 2013, https://simonmayers.com/2013/09/01/the-resilient-myth-that-the-wiener-library-defends-g-k-chesterton-from-the-charge-of-antisemitism/ (downloaded 17 September 2013).

7. G. K. Chesterton, “The Horse and the Hedge,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 30 March 1933, 55.

8. G. K. Chesterton, “The Judaism of Hitler,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 20 July 1933, 311-312.

9. G. K. Chesterton, “A Queer Choice,” Straws in the Wind, G.K.’s Weekly, 29 November 1934, 207.

Israel Zangwill and G. K. Chesterton: Were they friends?

In a previous report I examined the resilient myth that the Wiener Library defends G. K. Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism. In this posting I raise a more complex question: what was the relationship that existed between the prominent Anglo-Jewish author, Israel Zangwill, and G. K. Chesterton?

Michael Coren stated in 1989 that Israel Zangwill was a friend of Chesterton, describing them as a “noted literary combination of the time.”[1] Joseph Pearce has likewise reported that Israel Zangwill was someone with whom Chesterton had “remained good friends from the early years of the century until Zangwill’s death in 1926.”[2] One of the pieces of evidence of a friendship, circumstantial at best, is a photograph of Chesterton and Zangwill walking side by side after leaving a parliamentary select committee about the censorship of stage plays on 24 September 1909. The photograph was originally used for the front cover of the Daily Mirror on 25 September 1909. As they were both prominent authors, it is hardly shocking that they would both attend and give evidence at such a gathering. The photograph probably demonstrates little beyond that they shared an interest in government censorship and that they left the meeting at the same time (there is simply no way to tell for sure). According to an entire issue of Gilbert Magazine (2008) that was dedicated to defending Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism, Zangwill and Chesterton “had respect and admiration for one another.”[3] The photograph of them leaving the select committee on censorship was used as the front cover of the issue of Gilbert Magazine.[4] It has also been used in a number of other books and periodicals about Chesterton.

Chesterton and Zangwill after a parliamentary select committee about the censorship of stage plays on 24 September 1909

Prior to 1915, Chesterton had on occasion referred to Zangwill in positive terms, describing him as a “great Jew,” “a very earnest thinker,” and the “nobler sort of Jew.”[5] Likewise, Zangwill wrote a letter in 1914 and another in January 1915 which together suggest that an amicable relationship may have existed for a time (possibly until 1916). In 1914, he wrote to apologise for not being able to attend a public debate with Chesterton and several other people about the veracity of miracles. The letter was friendly though somewhat equivocal in its expressed sympathy for Chesterton’s play.[6] On 25 November 1914, Chesterton was overcome by dizziness whilst presenting to students at Oxford. Later that day he collapsed at home. He was critically ill, and it was feared that he might not survive. Whilst he did not fully recover until Easter, his wife reported on 18 January 1915 that he was showing some signs of recovery.[7] On 19 January, Israel Zangwill wrote a letter to Frances Chesterton, in which he expressed his pleasure at hearing that her husband was on the mend.[8]

Whatever the nature of their relationship, it did not prevent Chesterton from accusing Zangwill in 1917 of being “Pro-German; or at any rate very insufficiently Pro-Ally.” He suggested that “Mr. Zangwill, then, is practically Pro-German, though he probably means at most to be Pro-Jew.”[9] Their so-called friendship also did not prevent Zangwill from describing Chesterton as an antisemite. In The War for the World (1916), Zangwill dismissed the New Witness as the magazine of a “band of Jew-baiters,” whose “anti-Semitism” is rooted in “rancour, ignorance, envy, and mediaeval prejudice.” He suggested that G. K. Chesterton provided the “intellectual side” of the movement, which was, he concluded, “not strong except in names.” He stated that “Mr. G. K. Chesterton has tried to give it some rational basis by the allegation that the Jew’s intellect is so disruptive and sceptical. The Jew is even capable, he says, of urging that in some other planet two and two may perhaps make five.” Zangwill stated that the “conductors” of The New Witness would “do better to call it The False Witness.”[10] In 1920, Zangwill stated: “Yet in Mr. Chesterton’s own organ, The New Witness – the change of whose name to The False Witness I have already recommended – the most paradoxical accusations against the Jew find Christian hospitality.”[11]

In February 1921, in a letter to the editor of the Spectator, Zangwill described the proposal by Chesterton’s close friend, Hilaire Belloc, that Jews living in Great Britain should be characterised as a separate nationality, with special “disabilities and privileges,” as “ridiculously retrograde.”[12] Zangwill criticised Belloc’s scheme of “re-established Ghettos” in other articles, letters and notes in 1922. [13] Zangwill also observed in his letter to the Spectator, quite correctly, that Belloc’s “fellow-fantast, Mr. Chesterton, would revive the Jewish badge and have English Jews dressed as Arabs.”[12] This was a reference to a proposal by G. K. Chesterton in 1913 and again in 1920 that the Jews of England should be required to wear distinctive dress (he suggested the robes of an Arab).[14] According to Chesterton:

“But let there be one single-clause bill; one simple and sweeping law about Jews, and no other. Be it enacted, by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the Commons in Parliament assembled, that every Jew must be dressed like an Arab. Let him sit on the Woolsack, but let him sit there dressed as an Arab. Let him preach in St. Paul’s Cathedral, but let him preach there dressed as an Arab. It is not my point at present to dwell on the pleasing if flippant fancy of how much this would transform the political scene; of the dapper figure of Sir Herbert Samuel swathed as a Bedouin, or Sir Alfred Mond gaining a yet greater grandeur from the gorgeous and trailing robes of the East. If my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.”[15]

Whilst these letters and articles do not disprove the argument that Zangwill and Chesterton had an amicable relationship, at least for a time, they do suggest that Zangwill did not believe that Chesterton was guiltless of antisemitism. If Zangwill considered Chesterton a friend after 1915, let alone a pro-Jewish friend, he had a strange way of showing it. At the very least they problematize the argument that Chesterton could not have been antisemitic on the grounds that Zangwill was his friend, as from 1916 onwards Zangwill clearly came to perceive and describe Chesterton as an antisemite.

I would love to hear from anyone that has found any other evidence of a friendship or enmity between Zangwill and Chesterton (please click here to contact me).

Notes for the claim that Chesterton and the Anglo Jewish author Israel Zangwill were friends

[2] Joseph Pearce, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), p.446.

[3] Sean P. Dailey, “Tremendous Trifles,” Gilbert Magazine 12, no. 2&3 (November/December 2008), p.4. Gilbert Magazine is the periodical of the American Chesterton Society.

[5] See G. K. Chesterton, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1911), xi; Letter from G. K. Chesterton to the Editor, Jewish Chronicle, 16 June 1911, p.39; G. K. Chesterton, Our Notebook, Illustrated London News, 28 February 1914, p.322.

[6] According to Zangwill, Chesterton was “putting back the clock of philosophy even while he [was] putting forward the clock of drama. My satisfaction with the success of his play would thus be marred were it not that people enjoy it without understanding what Mr. Chesterton is driving at.” The letter is cited in G. K. Chesterton, Joseph McCabe, Hilaire Belloc, et al., Do Miracles Happen? (London: Christian Commonwealth, [1914]), p.23. The letter is also quoted by Joseph Pearce in Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), p.205.

[7] See Joseph Pearce, Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), pp.213-220 and Dudley Barker, G. K. Chesterton: A Biography (London: Constable, 1973), pp.226-230.

[8] Letter from Israel Zangwill to Frances Chesterton, 19 January 1915, ADD MS 73454, fol. 44, G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library, London.

[9] G. K. Chesterton, “Mr. Zangwill on Patriotism,” At the Sign of the World’s End, New Witness, 18 October 1917, pp.586-587.

[11] Israel Zangwill, “The Jewish Bogey (July 1920),” in Maurice Simon, ed., Speeches, Articles and Letters of Israel Zangwill (London: Soncino Press, 1937), p.103.

[12] Letter from Israel Zangwill to the Editor, “Problems of Zionism,” Spectator, 26 February 1921, p.263. In this letter, he went on to state that the so-called Jewish problem does “not concern Mr. Belloc, and I would respectfully suggest to him to mind his own business.” See also “Mr. Zangwill and Zionism,” Jewish Guardian, 4 March 1921, p.1.